Moral Intuitions

A basic insight of social psychology is that our beliefs and attitudes about ethical-moral issues are largely influenced by “fast thinking“. People tend to quickly decide what is morally “right” and “wrong” through intuition and emotion, and only then, through conscious, rationalizing thinking, to find reasons that support their initial intuitions.

This is not necessarily a bad thing! After all, intuitions and emotions serve important functions, and without them, people would hardly be motivated to spend time and energy to work towards perceived problems in the social groups they are a part of.

Through a variety of studies, the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt and colleagues found that people of all backgrounds seem to share a set of moral intuitions.

According to this, people have similar abilities to react emotionally and intuitively to certain social situations. However, each culture or community forms its own “moral framework” out of these moral intuitions, shaped by (or even as adaptation to) historical and socio-ecological realities. Thus, people and groups of people differ in the way they perceive and react to social situations.

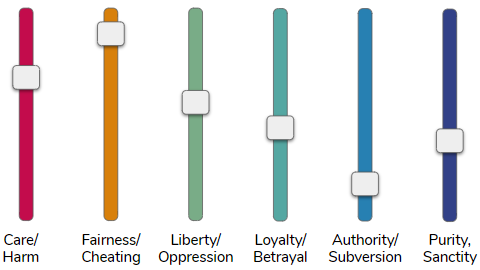

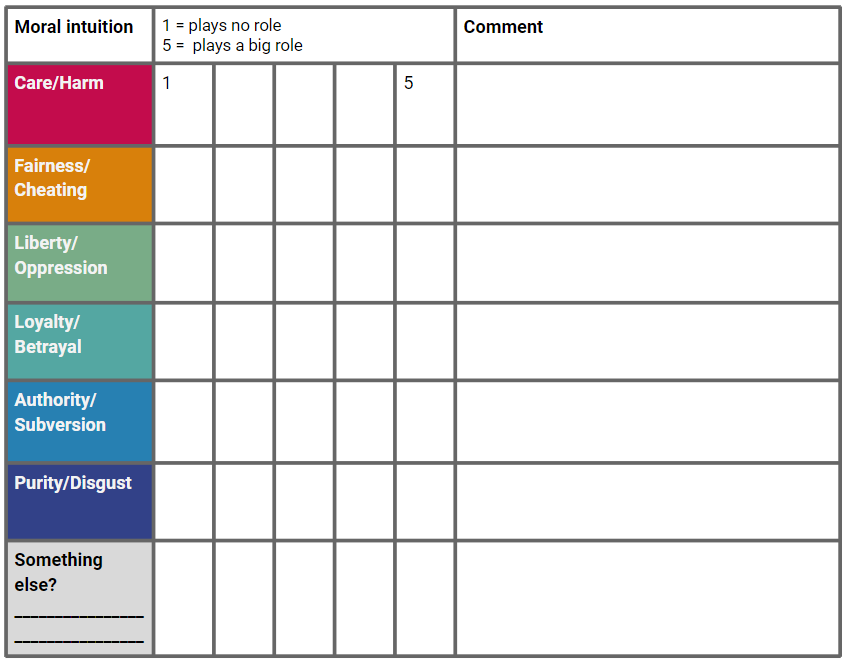

The following six moral intuitions have been identified so far:

Care / Harm – It is important to humans that no harm is done to them and others in “their group”.

Fairness / Cheating– It is important to humans that they and others in “their group” are treated fairly.

Freedom / Oppression – it is important to humans that they and others in “their group” are not oppressed and deprived of their freedoms.

Loyalty / Betrayal – It is important for humans to be committed to “their group” and that “their group” is not deceived.

Authority / Submission – It is important to humans that traditions, leadership and hierarchies in “their group” are respected.

Purity & Sanctity / Disgust & Degradation – It is important to humans that all behave, clothe, talk, eat, …. according to certain rules and norms that are considered “pure”, “sacred”, “proper” or “respectful”.

You can certainly identify other moral intuitions, depending on how narrowly or broadly you define them. For example, some people have suggested moral intuitions for “truth,” honesty”, “honor” or “property/ownershup” (more here).

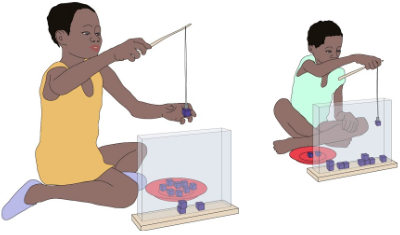

Six important human moral intuitions. Source: adapted from Grinberg et al. (2018). OpenMind TM Workshop Facilitator Guide

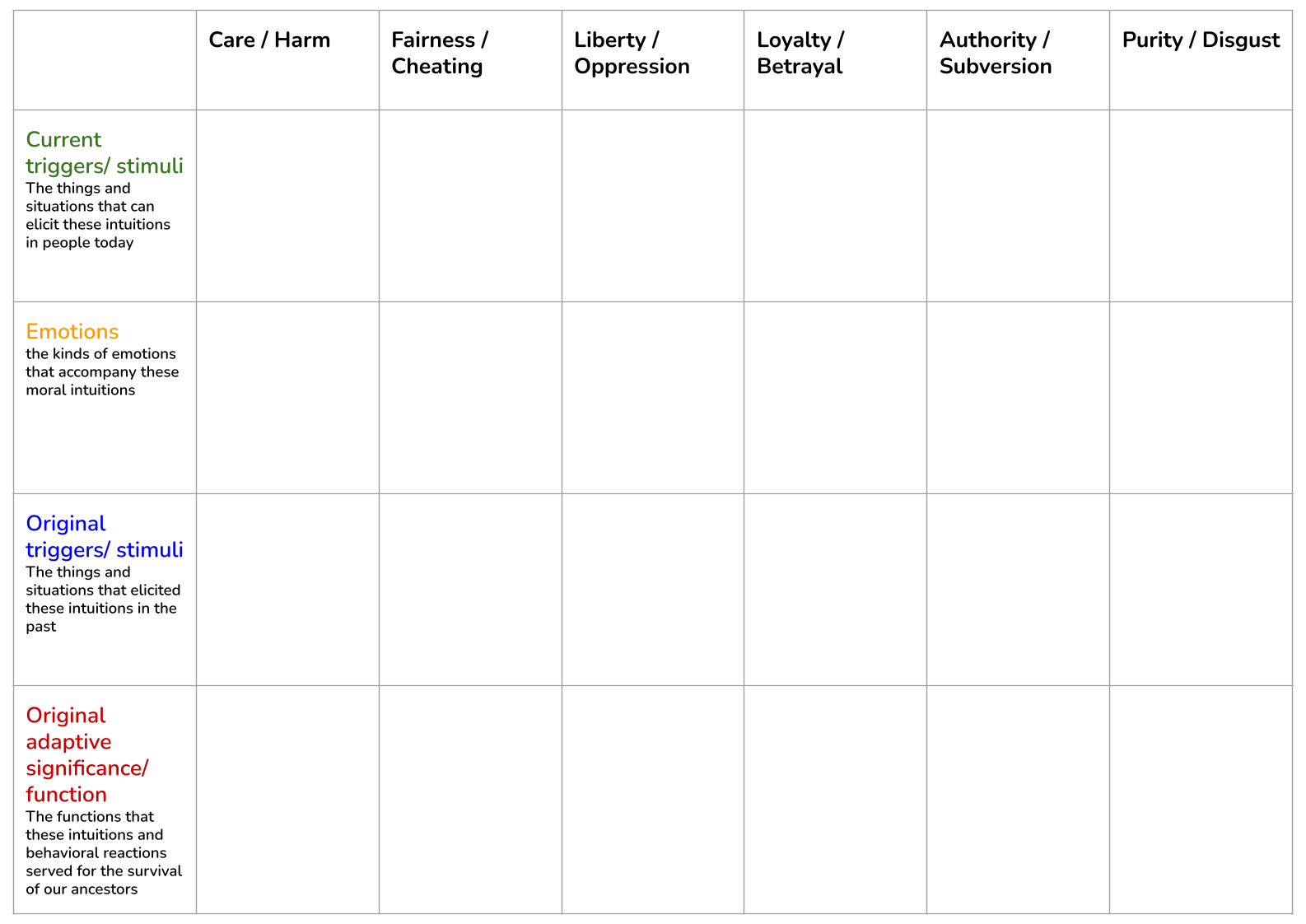

Moral intuitions handout

An overview of six important human moral intuitions

Noticing moral intuitions

Students identify the moral intuitions underlying people’s opinions in quoted texts and images.

It can be helpful to think of our moral intuitions like the different filters of a sound equalizer. We tend to amplify, reduce, and mix certain intuitions over others in a particular context or moral issue. Humans will differ in how they mix the moral intuitions!

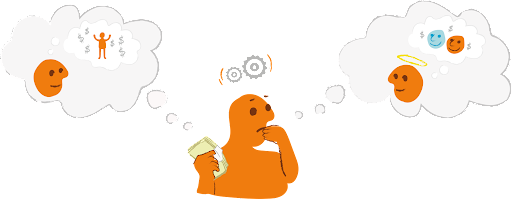

Analogy of "moral taste buds"

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt compares our moral intuitions with our taste buds. This analogy may help us to understand the evolutionary origins and the individual development of moral intuitions, as well as the variation in “moral tastes” among humans.

“We humans all have the same five taste receptors, but we don’t all like the same foods. (…) Just knowing that everyone has sweetness receptors can’t tell you why one person prefers Thai food to Mexican. ( …) It’s the same for moral judgments. To understand why people are so divided by moral issues, we can start with an exploration of our common evolutionary heritage, but we’ll also have to examine the history of each culture and the childhood socialization of each individual within that culture.”

“In this analogy, morality is like cuisine: it’s a cultural construction, influenced by accidents of environment and history, but it’s not so flexible that anything goes. You can’t have a cuisine based on tree bark, nor can you have one based primarily on bitter tastes. Cuisines vary, but they all must please tongues equipped with the same five taste receptors. Moral matrices vary, but they all must please righteous minds equipped with the same six social receptors.”

Source: Haidt (2012). The righteous mind. Why good people are divided by politics and religion. p. 113, 114.

Moral taste buds

In this lesson students explore the causes and functions of, as well as ways to flexibly relate to our moral intuitions by engaging the analogy to our taste buds.

Causes of our moral intuitions

Where do our moral intuitions come from and why do we have them? These questions about why and where we can answer in different ways (see also: Tinbergen’s questions):

Which immediate environmental influences triggered these intuitions? With which emotions and reactions are they connected? What happens in the brain and body when people judge something as morally good or bad?

Which influences and experiences in the individual development and in the social-cultural environment have contributed to the fact that these intuitions are triggered by certain environmental influences?

What is the evolutionary origin of these intutions? Do we share these moral intutions with other species? Why, or why not? When in evolutionary history did these moral intuitions emerge?

Did these intuitions fulfill important functions for our ancestors throughout evolutionary history? Do they fulfill important functions for humans today?

Because of our evolutionary history, we humans are highly social beings, and our social intuitions and emotions are part of our evolutionary heritage. They helped our ancestors to navigate in their social environment, to evaluate the social behavior of others and, where appropriate, to respond to it, and thus to regulate the life in the group. Is this person going to harm us? Is my child well? Is that unfair? Is this betrayal? Does this person belong to a dangerous group? Does everyone behave according to the rules? Am I good enough for my group? Are the others good enough for my group? Is someone taking advantage of us? Whose fault is it? etc.

So the moral intuitions fulfilled and still fulfill important functions for our social life in a group. However, like other cognitive biases, they can also lead to negative consequences under certain conditions.

Causes of our moral intuitions

In this lesson students explore the causes of our moral intuitions with the help of a sorting activity and reflection questions.

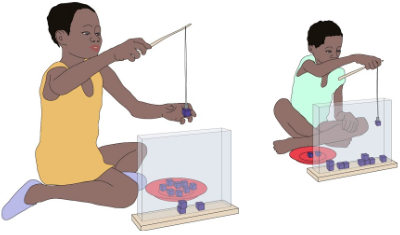

Born good? Babies help unlock the origins of morality

Can infants already distinguish between what is morally right and wrong? This video explores experiments with babies to answer these questions.

“Fair” does not always mean the same thing

These lesson materials introduce students to issues of fairness and various interpretations of it. Reflecting on results of a cross-cultural experiment with children, students discuss how we can use our understandings to create a more fair world.

In this video the moral intuitions, their functions and evolutionary origins are dicussed.

Researchers study the behavior of infants to explore the early development of our sense of “good” and “bad”, and our tendency to distinguish between “us” and “the others”.

Sense of fairness

A sense of fairness is one of our human “moral intuitions”. Almost all people, regardless of their culture and social background, seem to have a sense of fairness, even if it manifests itself in very different situations and varies in strength.

What appears to be “fair” often depends on the context, the people concerned and the role one plays in the situation – for example, should everyone be treated exactly the same unconditionally, should those who “deserve” it be treated better, or should we treat those preferentially who are in need because of their situation? This ambiguity of “fairness” often leads to disagreements, and so our sense of fairness comes into play in many debates in everyday life and in society. We also find the socio-emotional underpinnings to this sense of fairness in other species that live in groups.

Game theory: Ultimatum and Dictator game

A set of behavioral experiments across cultures that explore the human sense of fairness.

“Fair” does not always mean the same thing

These lesson materials introduce students to issues of fairness and various interpretations of it. Reflecting on results of a cross-cultural experiment with children, students discuss how we can use our understandings to create a more fair world.

"Morality binds and blinds"

Our social and moral intuitions seem to have played important roles in the life of our ancestors. Common beliefs about what is “true” and “important”, and what behaviors are “normal”, ensure that group members develop a common identity, are able to regulate their social life, work together and coordinate activities towards goals, resolve conflicts, and to take care of each other. Even today, people find themselves easily in groups of like-minded people, who gradually develop their own customs, languages, behaviors, and rules.

One’s own group, its customs and beliefs appear to be “good,” “normal,” and “justified,” and maybe even “superior” and morally on the “right” side. But the downside of this is that outsiders may seem all the more “different,” “bad,” “dangerous,” “ignorant,” and “morally reprehensible.” This is especially the case when the impression arises that “They” represent a danger or threat to the own group.

In psychology, this distorted perception and evaluation of one’s own and the other groups is called ethnocentrism. Ethnocentrism shapes the history of humanity and continues to be a challenge in today’s human societies. In times of uncertainty or perceived scarcity, people are particularly vulnerable to messages and clues that outsiders or dissenters pose a threat or are the perpetrators of perceived problems.

NetLogo: Evolution of ethnocentrism

This model simulates the biological evolution of ethnocentrism in a population made up of multiple ethnicities.

Function of cognitive biases

In this lesson students learn about the concept of cognitive biases as well as a number of important cognitive biases that may affect our well-being and social interactions, identify their causes in evolutionary history, their functions, and reflect on how to cope with cognitive biases.

Lesson idea: Students search in the media (or in historic sources) for texts or pictures (political speeches, blog posts, protest signs etc.) in which the author aims to exploit this human tendency by stirring up fear or aggression towards a certain group – which words, phrases or pictures are used? What effects are produced in the listeners / readers / viewers?

Practicing perspective taking

So it usually feels safe and pleasant to be with people who think, speak, behave, look or dress like ourelves, have the same preferences or come from the same “scene” as us. People usually have a great need for such social relationships and belonging to a group – this, too, is part of our evolutionary heritage.

But from time to time, we have to be able to leave this security zone, especially if in today’s society people from different backgrounds have to live together, tackle challenges, and make decisions together.

Understanding the origins of our own and other people’s opinions can help foster a change in perspective and a more constructive dialogue.

Discussion guide about moral issues

Lesson plan and worksheets to apply understandings of moral psychology in classroom discussions about ethical issues

True stories of people who left radical movements

In this unit students explore stories of people who have left a radical movement, or deliberately discuss with representatives of the “other side” and build respectful relationships. These let us explore the circumstances, experiences and insights about why prejudice, hatred and violence against other people or a group can arise and how they can dissolve again.