Life in groups

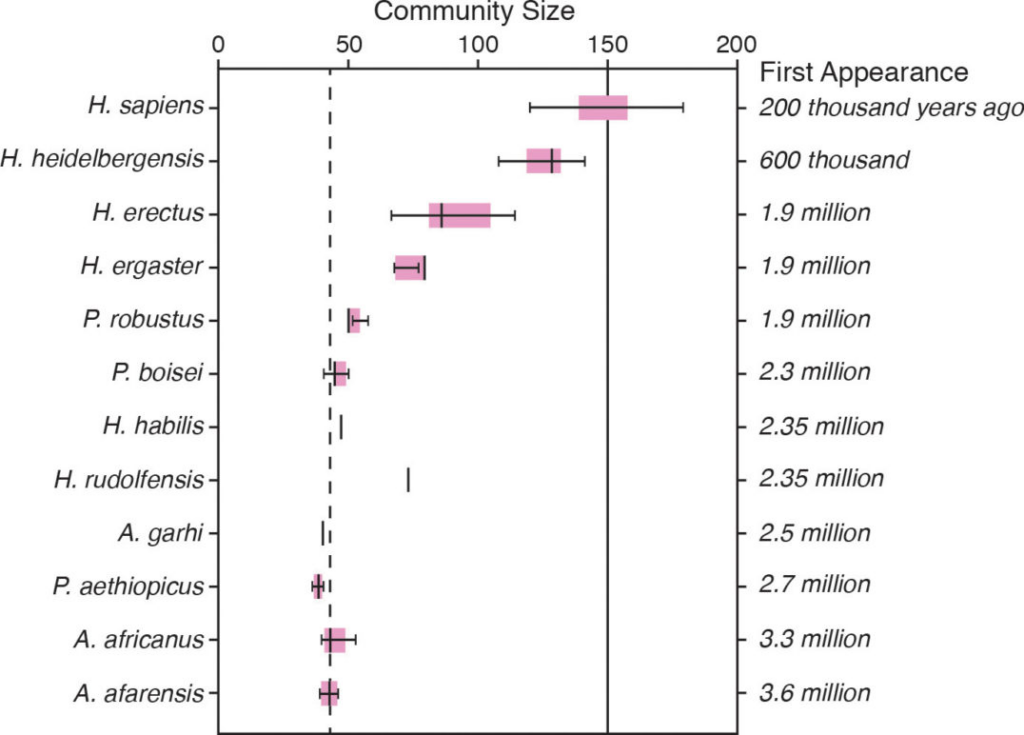

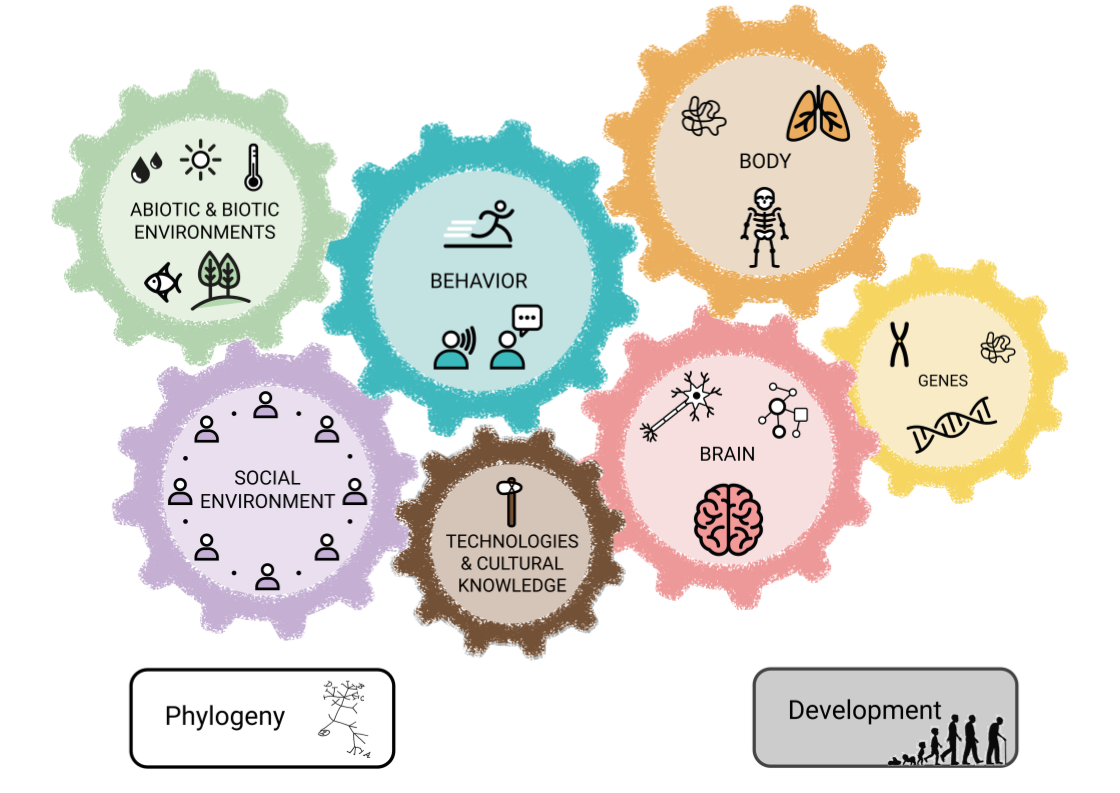

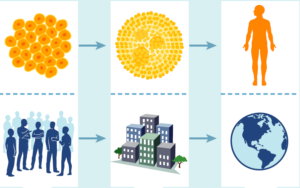

For our ancestors since Homo erectus, the survival and raising of offspring depended more and more on the group: foraging for food, raising children, making tools, and transmitting knowledge to others required cooperation and division of labor, and a group size in which all these tasks could be accomplished by their members. Everyone depended on each other, so they all “sat in the same boat“. Those groups that were better at cooperation and division of labor had better chances of survival and reproduction than other groups.

Such a situation of group life brings with it new challenges: procured resources have to be distributed in some way to all members, so that everyone gets as much as needed, even if he/she was not involved in the procurement of the resource. It must be prevented that individuals exploit the cooperation and thereby endanger the group. Conflicts should not even arise, and when they emerge, they must be resolved as quickly and efficiently as possible, so that they do not endanger the group. In those groups in which resources were distributed proportionally to all in a more efficient manner, and where fewer conflicts occurred or conflicts were resolved more efficiently, members had better chances of survival and reproduction than in other groups.

Among these groups, those had fewer conflicts or were able to resolve them more effectively, whose members had certain social skills and in which certain social norms influenced the behavior of members in a particular way.

Anthropologists and behavioral researchers suggest that under these social conditions, many of the social behaviors and cognitions of humans began to evolve through natural selection: social emotions and moral intuitions such as empathy, compassion, sense of fairness, outrage, envy, guilt and shame; motivation to share resources and information and for mutual help; a tendency to imitate the majority of the group and thereby establish social norms of behavior in a group; as well as a social temperament that motivates us to social encounters and gives us a need for group affiliation.

According to some anthropologists, all these challenges of a more complex group life also contributed to the selection pressures for a larger brain throughout our evolution.

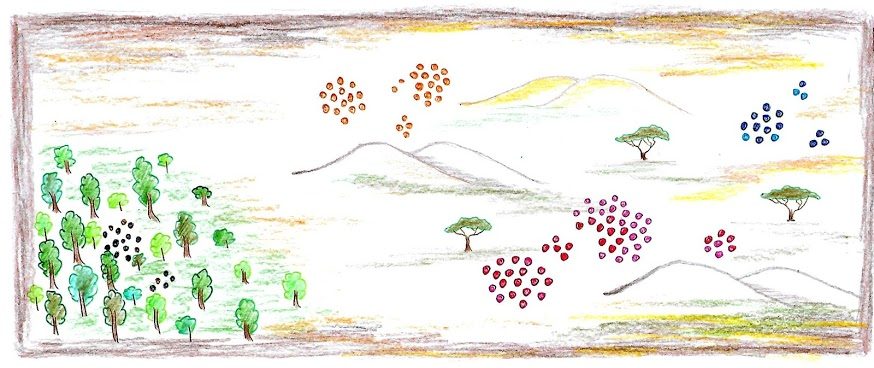

Image source: Dustin Eirdosh

Even in infancy, we humans already have special social perceptions: we can already distinguish whether someone behaves “good” or “bad” towards others. And we prefer those who are nice to others.

It seems that these abilities develop in the very first months of life, even before the influence of the social and cultural environment significantly shapes our behavior.

Similar videos:

- Magazine – Can Babies Tell Right From Wrong? | The New York Times https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HBW5vdhr_PA

- Good guys vs. bad guys: How early do babies know the difference? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ki1zyu81iMg

- Are babies born knowing right from wrong? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T_KKrdK1cJY

- Are babies born with a type of bias? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3EoNYklyShs

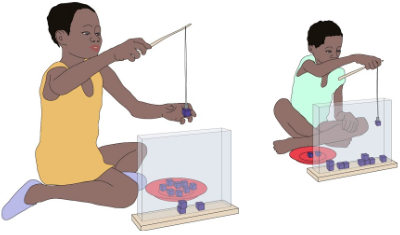

Video, Worksheets: Experiments on the social behavior of babies

Using puppets psychologists explore what small children as young as a few months old think about their social environment and whether they can distinguish between “good” and “bad”.

Even as small children, we humans have the ability to perceive that others need help. We seem to have this in common with chimpanzees. But we humans have a particularly high motivation to help others.

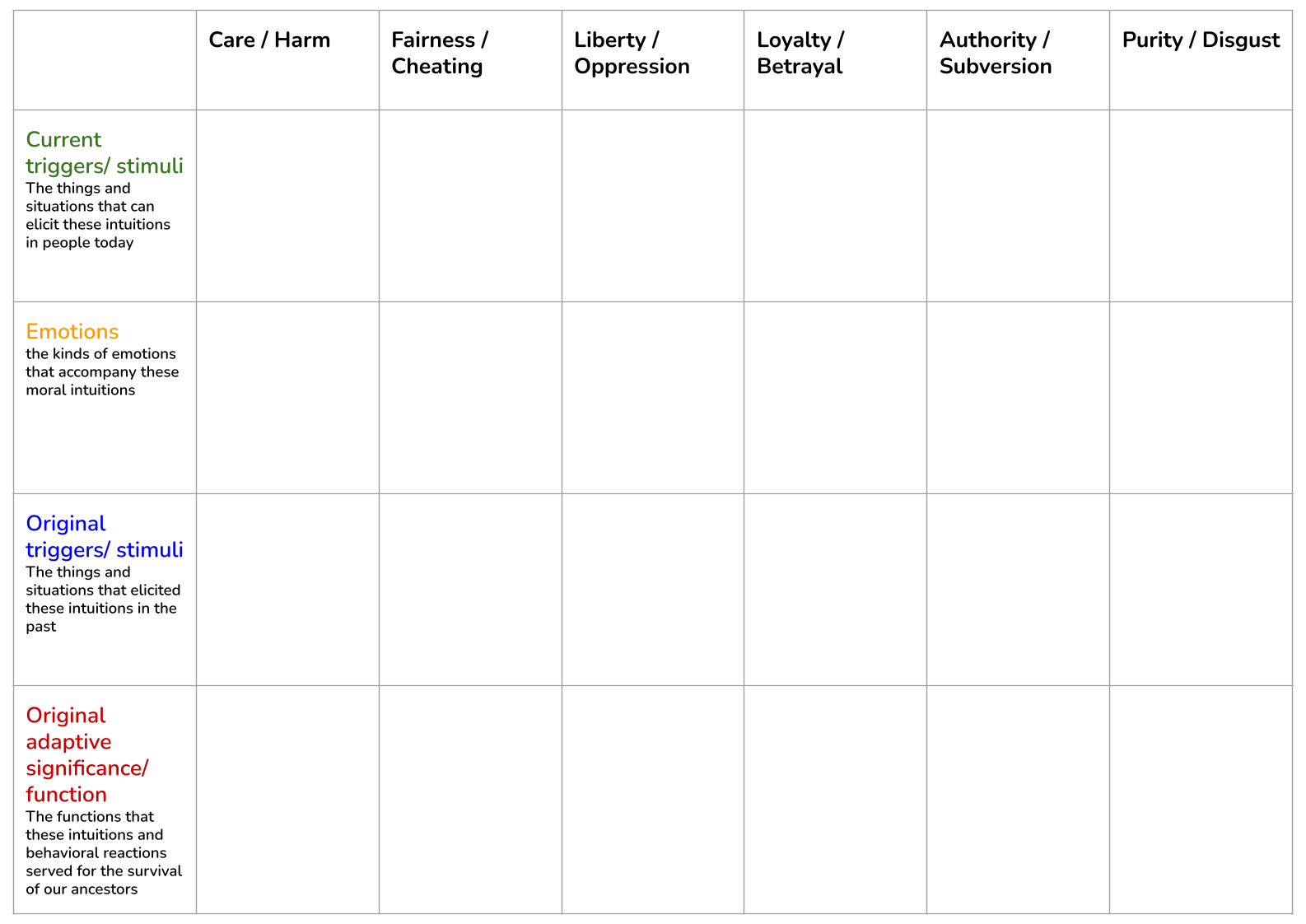

Causes of our moral intuitions

In this lesson students explore the causes of our moral intuitions with the help of a sorting activity and reflection questions.

Game theory: Ultimatum and Dictator game

A set of behavioral experiments across cultures that explore the human sense of fairness.

“Fair” does not always mean the same thing

These lesson materials introduce students to issues of fairness and various interpretations of it. Reflecting on results of a cross-cultural experiment with children, students discuss how we can use our understandings to create a more fair world.

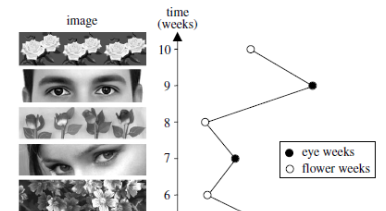

Perception of eyes and prosocial behavior

A behavioral experiment that tells us about the role of unconscious perception, particularly the perception of human eyes, on human social behavior.

- Decety & Cowell (2016). Our Brains are Wired for Morality: Evolution, Development, and Neuroscience (Frontiers for Young Minds article for 12-13 year olds)

- That’s Not Fair! Children in different cultures have different standards of fairness (Psychology Today article)

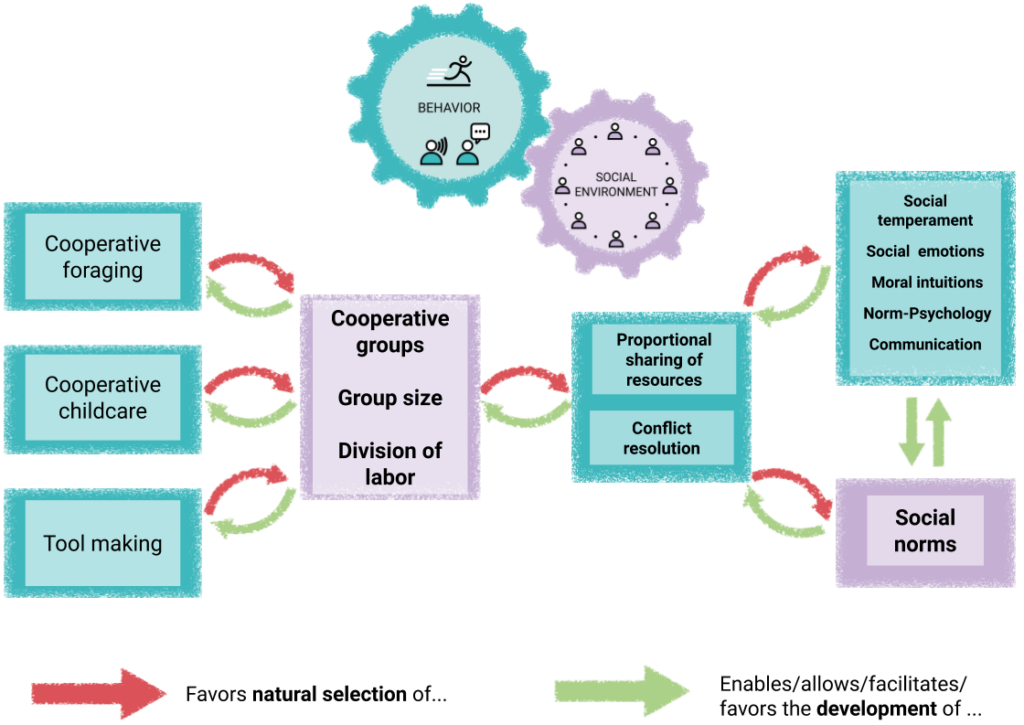

Causal map for life in groups

As humans developed adaptive responses to the conditions of the savanna, the behaviors involved in cooperative foraging, cooperative childcare, and tool making, all produced a selective advantage for larger, more cooperative groups capable of dividing labor and resources. Those groups that achieved larger scales of cooperation, with resources shared among all group members, and with fast and fair resolution of conflicts, would have had still a further fitness advantage, with members of those groups suriving and leaving more offspring than those of less cooperative groups. Among those larger-scale cooperative groups, individuals with social temperaments, emotions/intutions, and communication skills enabling them to avoid or resolve conflict, to ensure sharing of resources, and to adopt and enforce social norms, would have had still further fitness advantage both within their cooperative group, and relative to conspecfics in less cooperative groups. In those groups who established social norms of behavior that enabled the sharing of resources and resolution of conflicts, individuals would have had higher chances of survival and reproduction than individuals in other groups.

Genes that are involved in the development of these behavioral and cognitive skills and dispositions, would have spread in the population of our ancestors (not shown in this causal map).

Causal maps on the evolution of human traits

All causal maps on human evolution in one Google slide file

The environmental conditions of the savanna required cooperation. Among the different hominin groups, some could work better together than others, e.g. because there were differences in their temperament, behavior, ability to communicate, or because in their groups certain norms and traditions were established, which caused a relatively conflict-free coexistence.

Hunter-gatherers and egalitarian social organization

Homo erectus probably already lived in hunter-gatherer groups, whose social organization was similar to the still existing hunter-gatherer societies of today. Anthropologists are therefore particularly interested in studying the lifestyle of these hunter-gatherers who exist today, because they can provide us with information about the ways of life of our ancestors living 2 million years ago.

Hunter-gatherer societies are characterized, among others, by an egalitarian social organization (egalitarian or equal, from french égal, latin aequalitas) in which, unlike in chimpanzee groups, there is no social hierarchy and no dominance by one or a few individuals. Valuable resources such as meat are shared amongst everyone in the group. This does not mean that there are no conflicts or attempts by individuals to dominate the group or to seize more resources! Rather, there are conflict resolution mechanisms that ensure that such attempts by “bullies” are unsuccessful and do not harm the group.

Conflicts are often resolved without violence through threats, public denunciations and negotiations. Repeated or severe violations will gradually lead to harsher punishments, if necessary until expulsion from the group (this would mean death for our ancestors because survival depended on the group), or even killing. Thus, dominant or selfish actions of individuals are suppressed or marginalized through group collaboration. There are also similar dynamics like this, but on a smaller scale, among chimpanzees, when two or three lower ranking individuals form coalitions in order to take on a dominant. In humans, better weapons and throwing skill also gave greater power to the group over physically stronger “alpha males”. So the social hierarchy that we find among chimpanzees has in some ways been turned “upside down” in hunter-gatherer groups – the group dominates over the tyrant and keeps him in check. This ensured the survival of the entire group.

Life in groups and conflict resolution

A reading text about the challenges of life in groups and how groups across biology have found ways to solve these challenges.

References

- Bateson, M., Nettle, D., & Roberts, G. (2006). Cues of being watched enhance cooperation in a real-world setting. Biology Letters, 2(3), 412–414. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2006.0509

- Boehm, C. (1999). Hierarchy in the Forest. The Evolution of Egalitarian Behavior. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press.

- Chudek, M., & Henrich, J. (2011). Culture-gene coevolution, norm-psychology and the emergence of human prosociality. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15(5), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2011.03.003

- Gintis, H., van Schaik, C. P., & Boehm, C. (2015). Zoon Politikon. The Evolutionary Origins of Human Political Systems. Current Anthropology, 56(3), 327–353. https://doi.org/10.1086/681217

- Hamlin, J. K., Wynn, K., Bloom, P., & Mahajan, N. (2011). How infants and toddlers react to antisocial others. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(50), 19931–19936. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1110306108

- Hamlin, J. K., & Wynn, K. (2011). Young infants prefer prosocial to antisocial others. Cogn Dev., 26(1), 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2010.09.001

- Henrich, J., Boyd, R. T., Bowles, S., Camerer, C. F., Fehr, E., & Gintis, H. (2004). Foundations of Human Sociality. Economic Experiments and Ethnographic Evidence from Fifteen Small-Scale Societies. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press.

- Henrich, J., Boyd, R. T., Bowles, S., Camerer, C., Fehr, E., Gintis, H., … Tracer, D. (2005). “Economic man” in cross-cultural perspective: Behavioral experiments in 15 small-scale societies. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 28, 795–855. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X05000142

- Henrich, J., McElreath, R., Barr, A., Ensminger, J., Barrett, C., Bolyanatz, A., … Ziker, J. (2006). Costly Punishment across Human Societies. Science, 312(5781), 1767–1770. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1127333

- Henrich, J., Ensminger, J., Mcelreath, R., Barr, A., Barrett, C., Bolyanatz, A., … Gwako, E. (2010). Markets, Religion, Community Size, and the Evolution of Fairness and Punishment. Science, 1480(5972), 1480–1484. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1182238

- Tomasello, M. (2009). Why we cooperate. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press.

- Tomasello, M., Melis, A. P., Tennie, C., Wyman, E., & Herrmann, E. (2012). Two Key Steps in the Evolution of Human Cooperation. The Interdependence Hypothesis. Current Anthropology, 53(6), 673–692. https://doi.org/10.1086/668207