Pedagogical Approaches

We strive to integrate best pedagogical practices from a range of schools of thought into the design of lesson materials and curricula, and aim to support educators in using a variety of tried and tested approaches and perspectives in education.

In the 21st century, educators have become aware that the pedagogical approach of direct instruction and transmission of information that has been prevalent in formal schooling in the 20th century, is not appropriate for developing the kinds of competencies that are necessary for students to succeed and to have a positive influence in their communities.

Calls for more situated, authentic, experiential, transformative pedagogical approaches have therefore had an influence in education innovation movements in the last decades.

Unfortunately, discourse in education is often characterized by a battle between different camps swearing by a particular pedagogical approach, such as the value and need of direct instruction on the one hand, or the value and need of project-based, experiential, authentic experience and critical reflection on the other hand.

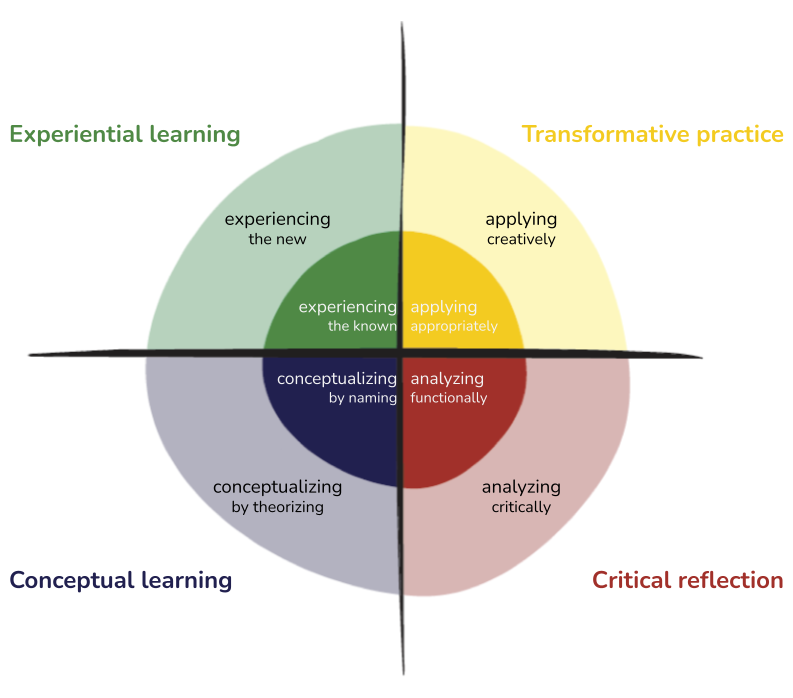

In contrast, the “multi-pedagogical” or “reflexive pedagogy” view promoted by Bill Cope and Mary Kalantzis within their Learning by Design project considers all of these different pedagogical approaches as playing an important role in learning – this is because learning involves different processes – different ways of knowing – including direct experience, conceptual understanding, critical reflection, and appropriate and creative application of the learned, all of which can best be cultivated by different pedagogical methods and approaches.

The point of good education is not to choose one over another and disregard the rest, but to choose the right approach for the right moment in the learning process, and to weave them all together in the best way such that learning is maximized.

The different knowledge processes that can be involved in learning and that require different pedagogical approaches are presented in the diagram to the right.

Specific teaching and learning methods can be woven into the design of a lesson and unit to build on and support these knowledge processes.

Image source: adapted from Cope & Kalantzis (2020), https://newlearningonline.com/learning-by-design/pedagogy

Experiencing

- the known – learners reflect on their own familiar experiences, interests and perspectives.

- the new – learners observe or take part in something that is unfamiliar; they are immersed in new situations or contents.

Because human behavior is at the center of all of our lives and everyday experience, many opportunities exist to let students bring this everyday understanding into the classroom when exploring a particular set of behaviors. For example, through reflection and discussion questions:

- Think of a situation when you felt treated unfairly. How did it make you feel? How did you behave?

- Do you think all humans care about fairness? Why, or why not?

- Might humans have different views about what is fair in a particular situation? Why, or why not?

Through the methods and insights of behavioral science, many opportunities also exist that allow students to experience new aspects of human behavior in the classroom. Content anchors such as classroom games, computer simulations, behavioral experiments and observations across species, development or cultures, archeological findings, and even exploring what their mind does in the moment.

Texts, images, videos, or social media content can also serve to expose students to particular aspects of what humans do.

Community science investigations can also help students observe and explore the behaviors of people in their communities, including their needs, interests, values, and goals.

Conceptualizing

- by naming – learners acquire new concepts and/or extend, deepen, and enrich their prior understanding of known concepts, by exploring examples and attributes and constructing definitions.

- by theory – learners make generalisations by connecting concepts in relationships

Even though human behavior is at the center of all of our lives and everyday experience, we might not have an explicit, well developed, or particularly helpful understanding about what human behavior actually is (and what it is not), how it is caused, why it varies among humans, or how we can change it towards what we care about.

This is why the focus on human behavior and associated concepts is the first Design Principle of our educational design concept.

In order to reflect on human behavior, students need to first develop and make visible their own understandings of core concepts by reflecting on questions such as:

- What is human behavior? What are some examples, and non-examples, of human behavior? What characterizes human behavior?

- What is sustainability?

- What is evolution? What is cultural evolution?

- What are human values? What are examples of human values? What characterizes human values?

- What is well-being?

- What is fairness?

Furthermore, students need to develop an understanding about how concepts relate to each other to form principles, generalizations, theories, such as:

- How does human behavior impact sustainable development?

- How does our human sense of fairness impact sustainable development?

- How can mindfulness influence human well-being and sustainable development?

- How do our behaviors impact the cultural evolution of our species?

- What conditions allow and hinder humans to cooperate towards common goals?

- How does our evolutionary past impact our behaviors today?

- How does our experience and learning impact our behaviors today?

Concept-based curriculum (Erickson et al., 2017) as well as teaching for conceptual understanding (Stern et al., 2017) and learning transfer (Stern et al., 2021) are approaches to designing curricula, units, lessons, and assessments that help achieve deeper and transferable understandings of concepts and general principles of a theme in students, where specific subject content and facts serve as a means to achieve such deeper understanding, rather than an end in itself.

Concept-based unit design and teaching for conceptual understanding provide us with well founded and popular frameworks for doing this conceptual clarification for education. Learn more about the basics of conceptual understanding from expert educator Julie Stern in the videos below. In these videos, Julie describes teaching for conceptual understanding of relationships between human actions and the environment. The OpenEvo educational design concept extends this foundation by focusing on understanding the complex causes and consequences of human behavior itself.

The Learning Transfer Mental Model from Stern et al (2021), which highlights how we can guide students to acquire, connect, and transfer their growing understandings of concepts and conceptual relationships.

Analyzing

- functionally – learners analyse logical connections, cause and effect, structure and function.

- critically – learners evaluate their own and other people’s perspectives, interests and motives.

The ability of students to analyze and reflect on the various causes and consequences of human behavior, the functions that particular behaviors have for humans in relation to their goals and values and in the context of their particular environment, is one of the core learning goals of OpenEvo.

This is also why exploring complex causality is one of the core design principles of our educational design concept.

Analyzing causes and consequences of human behavior is also a core aim of the behavioral sciences. Our collection of thinking tools reflect some of the tools and methods that scientists use for this analysis and that students can equally use when analyzing human behaviors across contexts.

- Tinbergen’s questions: a set of four broad questions that can help to map out the space of different causes that we need to explore in order to understand why humans behave the way they do in a particular situation

- Causal mapping: a simple toolkit to let students collect, visualize, discuss, analyze, and reflect the different causal relationships and complex interactions between human behaviors and other factors

- Payoff matrix: a simple tool to let students reflect on the beliefs, feelings, and goals underlying human motivations to behave in a certain way in a certain situation, and the emergent short-term and long-term outcomes their behaviors might create for themselves and others

- Noticing Tool: a tool to help students become aware of and interpret the functions of their own inner experiences and outer behaviors

Reflection prompts during and at the end of lessons encourage learners to make connections between the aspects of human behavior that have been explored, and the real world, including their own and other people’s goals and values.

Applying

- appropriately – learners apply new learning to real world situations and test their validity.

- creatively – learners make an intervention in the world which is innovative and creative, or transfer their learning to a different context

Students’ ability to apply new learning appropriately to new contexts is one of the core aims of education in general, and is represented by the third of our overarching design principles – Teach for Transfer.

We aim for students to be able to apply the conceptual understandings and skills that they develop around the nature of human behavior to situations in their everyday life and to real-world problems of sustainable development.

Thinking tools like analogy maps can help students in reflecting on the transfer of general principles and processes across a wide range of contexts and domains.

Finally, we want students to use their understandings of human behavior to identify and develop interventions and solutions to real-world problems.

For example:

- Students create a poster or presentation to raise awareness about the relationship between social inequality and human well-being, after they have explored behavioral science perspectives;

- Students discuss and create a campaign at their school to prevent people from joining extremist groups after exploring the stories about people joining and then leaving extremist movements;

- Students create and document a process in their next project group work that assures that all members of the group feel treated fairly and that everyone’s strengths, interests, needs and constraints are taken into account, after they explore the origins and variations in our human sense of fairness;

- Students design and carry out a Community Science project to find out what goals and values the people at their school have, what the meaning and purpose of school is for them and how they imagine their ideal school after they have learned how important shared goals and values are for successful cooperation and for the well-being of everyone in a community.

Within our educational design work we hypothesize that through the interplay of all these knowledge and learning processes, learners increasingly acquire a deeper, networked, helpful, and applicable understanding of human behavior, as well as skills and methods to notice, interpret, reflect, and shape human behavior – especially their own, in the service of valued living.

In this way, learners ultimately experience a transformation of their own consciousness as a human and their relationship to the world around them.

"[T]ransformative learning involves a deep structural shift in the basic premises of thought, feelings and actions. It is a shift of consciousness that dramatically and permanently alters our way of being in the world. Such a shift involves our understanding of ourselves and our self-location: our relationships with other humans and with the natural world."

Morrell & O’Connor (2002), p. xvii

"Imagine if we could teach young people to become mindful of the ways that symbols can dominate our interpretations of experience and can become unhelpful. They might then learn to use symbols like tools, and “put them down” when no longer useful. They might become less caught up in self-criticism, materialism and prejudice. Could they pass these lessons on to their children? Or imagine if all young people learned to judge their behavior in terms of how it served their values, and especially how it helped them build connection and love. Or imagine young people who understood that they are not fixed, and the future is not fixed, and they can improve themselves and this world. What might they teach their children?”

Ciarrochi & Hayes (2018), p. 121

"We would argue that there is a major difference between behavioral science (...) and every other area of scientific progress. (...) Most people who make daily use of the technologies that have so changed the world in the past century, need not understand the science that led to and underpins the efficacy of their computers, cell phones, televisions, automobiles, air conditioners, and so on. (...) The situation is a little different when it comes to the behavioral sciences (...). [T]ranslating the advances in scientific understanding of human development into comparable improvements in human well‐being requires that we get most people in society to understand – at least in rough outline – what humans need to thrive.”

Biglan et al. (2015), p. 537, 538

References and further information on pedagogy

Learning by Design

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (2015). A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies. Learning by Design. (B. Cope & M. Kalantzis, Eds.). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137539724

Cope, B., Kalantzis, M., & Smith, A. (2018). Pedagogies and Literacies, Disentangling the Historical Threads: An Interview with Bill Cope and Mary Kalantzis. Theory into Practice, 57(1), 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2017.1390332

Teaching for conceptual understanding and transfer of learning:

Stern, J., Ferraro, K., & Mohnkern, J. (2017). Tools for Teaching Conceptual Understanding, Secondary. Designing Lessons and Assessments for Deep Learning. Corwin.

https://edtosavetheworld.com resources, tools, online courses, and information on designing classroom activities and units for conceptual understanding and transfer

The Research Underpinnings of Learning That Transfers (LTT) https://edtosavetheworld.com/2021/03/21/the-research-underpinnings-of-learning-that-transfers-ltt/

Concept-based curriculum and instruction:

Erickson, H. L., Lanning, L. A., & French, R. (2017). Concept-Based Curriculum and Instruction for the Thinking Classroom (2nd ed.). Corwin.

Biglan, A., Zettle, R. D., Hayes, S. C., & Holmes, D. B. (2016). The Future of the Human Sciences and Society. In R. D. Zettle, S. C. Hayes, D. Barnes‐Holmes, & A. Biglan (Eds.), The Wiley Handbook of Contextual Behavioral Science (pp. 531–540). Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118489857.ch26

Ciarrochi, J. & Hayes, L. (2018). Shaping DNA (Discoverer, Noticer, and Advisor): A Contextual Behavioral Science Approach to Youth Intervention. In: Wilson, D.S. & Hayes, S.C. Evolution and Contextual Behavioral Science (pp. 107-124). Context Press.

Morrell, A., & O’Connor, M. (2002). Introduction. In O’Sullivan, E., Morrell, A., & O’Connor, M. (2002). Expanding the Boundaries of Transformative Learning Essays on Theory and Praxis. (E. O’Sullivan, A. Morrell, & M. O’Connor, Eds.). New York: Palgrave.