Social (In)Equality

For most of our evolutionary history, we humans have been living in small groups, with no more than a few dozen up to a hundred people. Any life in groups brings with it the potential for conflict and the challenge of how to distribute resources or how to make decisions.

We have evolved social behaviors that enable us to regulate social life in such small groups, including social emotions, a social temperament, moral intuitions such as a sense of fairness and a sense of liberty and autonomy, and a so-called norm-psychology – a tendency to learn and imitate the behaviors of the people around us, to consider these behaviors as “normal” and to be irritated if someone behaves in a way that doesn’t follow the group’s norms.

Today’s hunter gatherers give us some clues about the social organization that our species lived in throughout most of our history. Hunter-gatherers tend to live in egalitarian groups, meaning that there is no strong hierarchy and an equal distribution of resources. Attempts by individuals to dominate the group or hord resources are discouraged and punished by everyone else in the group.

However, with agriculture, the ability to store and accumulate valuable resources, division of labor, the first cities, our group sizes started to grow, from a few thousand to many thousands and finally millions of people. How can life in such groups be regulated? It seems that with the increase in group sizes, the leveling mechanisms that worked well in small hunter-gatherer groups did not work sufficiently anymore in such larger group, and with increasing group size came an increasing inequality in power and wealth.

Scientists are trying to better understand the factors that have lead to this departure from egalitarian hunter-gatherer origins and the spread of inequality throughout our history.

One such factor seems to be the ability to store, accumulate, and defend valuable resources, which became possible and important with the beginning of a sedentary lifestyle and agriculture. Another factor seems to be the inheritance or transmission of these resources to children (instead of redistributing them equally to everyone in the next generation). Whether or not wealth is inherited or redistributed in the population, and to what extend, is governed by more or less formal social norms and institutions (such as property rights, tax regulations for different sources of wealth, existence or absence of social welfare programs such as funding equal access to education and health care for all citizens).

These factors together led to a transition to greater inequality in the neolithic period, and to an increase in inequality over time, through a feedback loop – the more wealth someone has, the more access to power and education they have, and the more wealth they can accumulate (and transmit to their offspring) (see also: System archetype “Success to the Successful”). Over time, the rich get richer, and the poor get poorer.

However, in the last two centuries, there is also a decrease in inequality observable.

Life in groups and conflict resolution

A reading text about the challenges of life in groups and how groups across biology have found ways to solve these challenges.

“Fair” does not always mean the same thing

These lesson materials introduce students to issues of fairness and various interpretations of it. Reflecting on results of a cross-cultural experiment with children, students discuss how we can use our understandings to create a more fair world.

Two stories of capitalism

Students explore two contrasting stories about the benefits and failures of capitalism, identify the moral intuitions behind each story, and write a third story about capitalism that integrates aspects of both stories.

Goal 10 of Global Sustainable Development Goals is to reduce inequality within and between countries.

Will we be able to greatly reduce inequality within and between countries in the future?

How can we develop a system of wealth distribution within a country that is considered fair by everyone? (think about the interests of different people: those who gained wealth through hard work and investments and want to pass on this wealth to their children, those who inherited wealth from their parents, those who didn’t inherit anything or inherited debt from their parents, those who are not able to work for reasons outside their control …)

How can we develop a system of wealth distribution between countries that is considered fair by all? (think about the interests of people in different countries: those who are fortunate enough to live under favorable environmental conditions with lots of resources or without much harm from natural disasters; those who are unfortunately living under unfavorable environmental conditions; those who are fortunate to live in and “inherit” a country that gained wealth through extracting it from colonies, slavery or through war in the past; those that live in former colonies or are part of a group that was exploited in the past, … )

What is the relationship between equality and liberty? Does a more equal distribtution of wealth inevitably lead to less liberty for people? Does liberty to pursue different interests and activities inevitably lead to increasing inequality over time?

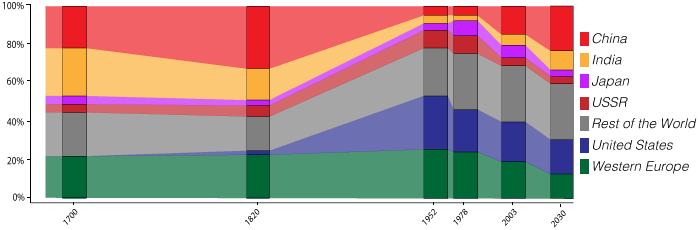

This graph shows the changing distribution of the global wealth (in percentage of total GDP) owned by different countries since 1700.

Measuring inequality

When we try to compare two countries, or two time periods, by their level of inequality within their population, we have to find a common measure.

One measure that scientists use to do this is called Gini coefficient. The higher the Gini coefficient, the higher the economic inequality in a population. A Gini coefficient of 1 (or: 100%) means that one person has all of the wealth and everybody else has nothing. A Gini coefficient of 0 means that everybody has exactly the same wealth. In reality, the Gini of a population is somewhere between these values.

The Gini coefficient does not really tell us exactly how income in a population is distributed – two different distributions can have the same Gini coefficient.

Another type of measure to compare economic inequality between populations are shares of income held by certain groups of the population.

The chart on the right shows the share of a country’s income held by the richest 10% of the population.

The closer that share is to 10%, the more equality there is between the richest people in the country and the rest of the population. (A share of 10% would mean that “the richest 10%” are in fact on average no more wealthy than the rest of the population.)

Social (in)equality and well-being

An important effect of social inequality that scientists are trying to understand is its relationship to measures of well-being.

For example, a number of studies have found that more unequal societies appear to have higher rates of obesity, mental illness, teenage births, homicides, imprisonment rates, lower levels of trust, lower life expectancy and lower student educational performance.

Goal 3 of Global Sustainable Development Goals is to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all humans at all ages.

If we know that our social environments, including socio-economic inequality, have a big impact on our physical and psychologcial health, how can we assure that the social environments we create do not have negative impacts on our health? What can we do to create healthy social environments in which everyone feels safe, a sense of belonging and has their needs taken care of

- at home?

- in our school?

- in our community?

- in our country?

- in the world?

Richard Wilkinson: How economic inequality harms societies.

Social scientist Richard Wilkinson presents his findings about the effects of economic inequality on social and psychological measures of well-being.

English transcript with graphs

Discussion questions:

- According to the researcher Richard Wilkinson, which indicators of social and psychological well-being are corrrelated with the degree of inequality in a country (and US state)?

- What are some explanations for how economic inequality might be causing such effects on human well-being?

- What can we do, as individuals and as a society, to increase equality within and between countries?

The Science Is In: Greater Equality Makes Societies Healthier and Richer. https://evonomics.com/wilkinson-pickett-income-inequality-fix-economy/ (this short articles presents similar arguments and evidence as the video above)

What does inequality do to our bodies and minds? A social psychologist and an epidemiologist discuss. https://ideas.ted.com/what-does-inequality-do-to-our-bodies-and-minds-a-social-psychologist-and-an-epidemiologist-discuss/

But what mechanisms could in fact be causing such effects of inequality on a society? Some mechanisms that have been proposed include:

- People with low socio-economic status have less access to resources, including health care and education.

- People with low status experience more uncertainty and less control over their lives. This affects stress which affects health and longevity. This is true not just for humans but also for other animals that live in social groups where hierarchies tend to form, creating social and psychological stress, such as in baboons.

- However, there also appear to be negative effects on society as a whole: not only those with a relatively low social status, but everybody becomes more competitive, more worried, more uncertain, and more stressed about one’s social status.

Generally, due to our evolutionary history as a highly social species, human well-being is greatly dependent on factors of a healthy and safe social environment, such as social cohesion, high levels of trust, solidarity, a sense of belonging and community. The more unequal a society, the more there is social division, hierarchy, coercion, discrimination, prejudice, uncertainty, and lack of trust in the social environment.

Furthermore, due to our evolutionary history as a highly social species, we humans have a hightened sense of fairness and other moral intuitions, such that we tend to compare ourselves to others in our social environment, and we care more about relative status and wealth than absolute wealth. The less we have compared to others within the group that we consider ourselves part of, the more frustrated we are.

"Once basic needs are met, poverty alone is not as predictive of poor health as is poverty amid plenty. (...) when there is considerable poverty amid plenty (i.e., high income inequality), people tend to decrease their investment in (and expectations of) the community, thereby reducing everyone’s quality of life. This decline results in more psychological stressors (because of a reduced collective sense of efficacy and control, greater need for vigilance amid increased crime, and so on) and less social support. Finally, amid the adverse community-wide consequences of income inequality and low social capital, the wealthy have disproportionate opportunities (both financial and otherwise) to obtain private means of stress-reduction, further decreasing their incentive to invest in public, community-wide means."

(Sapolsky, 2004, Social Status and Health in Humans and Other Animals, p. 411)

The neuroscientist and behavioral biologist Robert Sapolsky on the causes and functions of stress in animals.

Possible discussion question: Why does Robert Sapolsky think that Baboons are a good model to understand the causes of stress in humans?

see the full documentary “Stress – Portrait of a killer”: https://youtu.be/eYG0ZuTv5rs

see also: Mismatch? / Stress

Social (in)equality and political stability

Another important effect of social inequality that scientists are trying to understand is its relationship to political stability (which in turn seems to be related to measures of well-being).

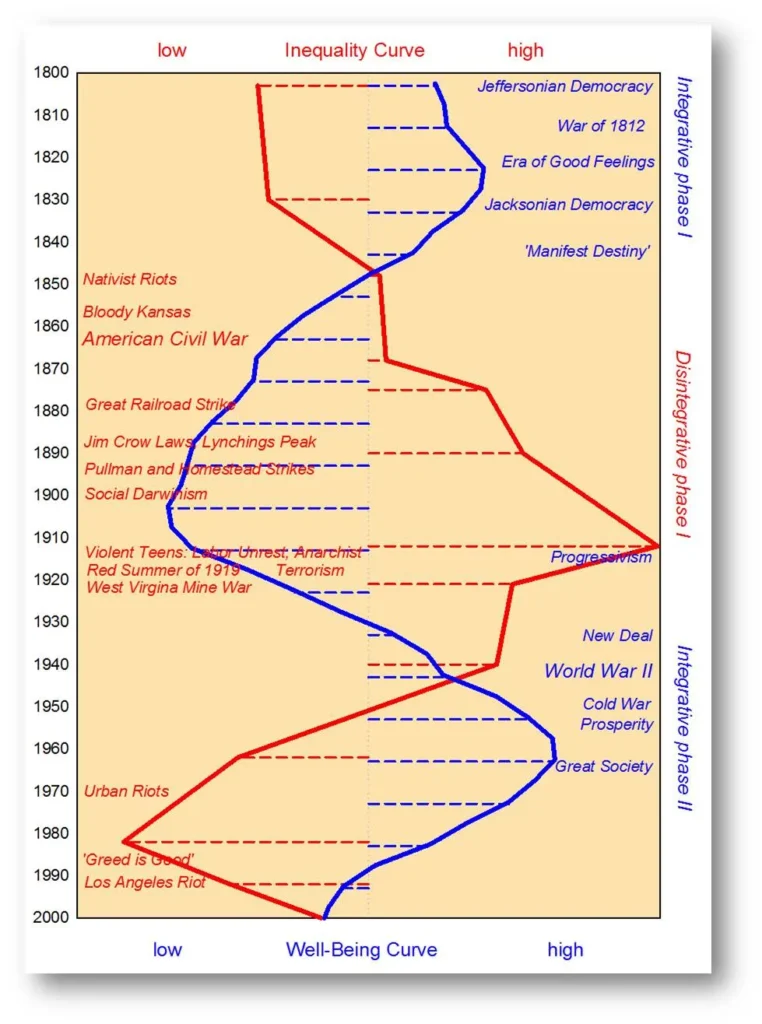

According to the historian Peter Turchin, the level of inequality in a society, indicators of well-being, and political stability seem to be correlated in long-term cycles through history.

Peter Turchin was originally an ecologists who now investigates human history through the lense of ecology – using mathematical models to capture and understand the rise and fall of societies and the long-term changes in measures of social organisation, political stability, and human well-being.

According to this more quantitative and mathematical study of history called Cliodynamics (named after Clio, the ancient Greek godess of history), just like ecological populations and ecosystems are complex systems, so societies can be understood as complex systems.

Just as in complex ecological systems, changes can be observed to follow certain regularities due to interactions of organisms and system feedback loops between factors (think for example, about predator-prey population dynamics), so in complex societies, changes can be observed to follow certain regularities due to interactions of many people and system feedback loops between factors in society.

Thus, in societies, measures of political stability, equality and well-being seem to be correlated and may be influencing each other over longer periods of time.

This does not mean that one can predict what exactly will happen where and when in such complex systems, neither in ecosystems nor in societies. However, understanding these larger dynamics can help us understand what we need to do to intervene in order to avoid unpreferable futures and make preferable futures more likely.

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20170418-how-western-civilisation-could-collapse

Measures of well-being and inequality in the US seem to be negatively correlated and seem to have changed in cycles over the last two centuries.

http://peterturchin.com/cliodynamica/the-double-helix-of-inequality-and-well-being/

"Our society, like all previous complex societies, is on a rollercoaster. Impersonal social forces bring us to the top; then comes the inevitable plunge. But the descent is not inevitable. Ours is the first society that can perceive how those forces operate, even if dimly. This means that we can avoid the worst — perhaps by switching to a less harrowing track, perhaps by redesigning the rollercoaster altogether. "

Peter Turchin (2013)

Goal 16 of Global Sustainable Development Goals is to promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels.

If we know that our social environments, including socio-economic inequality, have a negative impact on peace and political stability, how can we create healthy social environments in which everyone feels safe, a sense of belonging and has their needs taken care of

- at home?

- in the school?

- in our community?

- in our country?

- in the world?

Gender (In)equality

(Under construction)

Smuts, B. (1995). The evolutionary origins of patriarchy. Human Nature, 6(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02734133

Manning, J. T., Fink, B., & Trivers, R. (2014). Digit ratio (2D:4D) and gender inequalities across nations. Evolutionary Psychology : An International Journal of Evolutionary Approaches to Psychology and Behavior, 12(4), 757–768. https://doi.org/10.1177/147470491401200406

Goal 5 of Global Sustainable Development Goals is to achieve gender equality and empower people of all genders.

References and Links

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20170418-how-western-civilisation-could-collapse

https://evonomics.com/wilkinson-pickett-income-inequality-fix-economy/

https://www.un.org/development/desa/undesavoice/expert-voices/2020/01#48143

Borgerhoff Mulder, M., Bowles, S., Hertz, T., Bell, A., Beise, J., Fazzio, I., … Irons, W. (2010). Intergenerational Wealth Transmission and the Dynamics of Inequality in Small-Scale Societies. October, 326(5953), 682–688. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1178336

Hodgson, G. (2016). How capitalism actually generates more inequality. Why extending markets or increasing competition won’t reduce inequality. Evonomics. https://evonomics.com/how-capitalism-actually-generates-more-inequality/

Mattison, S. M., Smith, E. A., Shenk, M. K., & Cochrane, E. E. (2016). The evolution of inequality. Evolutionary Anthropology, 25(4), 184–199. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.21491

Sapolsky, R. M. (2004). Social Status and Health in Humans and Other Animals. Annual Review of Anthropology, 33(1), 393–418. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.144000

Schneider, S. M. (2019). Why Income Inequality Is Dissatisfying—Perceptions of Social Status and the Inequality-Satisfaction Link in Europe. European Sociological Review, 35(3), 409–430. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcz003

Spinney, L. (2012). Human Cycles. History as Science. Nature, 488(7409), 24–26. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/news/human-cycles-history-as-science-1.11078

Turchin, P. (2012). How Science Can Decode the Laws of History and Predict US Political Violence. Evonomics. https://evonomics.com/cliodynamics-can-science-decode-laws-history/

Turchin, P. (2013). Return of the oppressed. From the Roman Empire to our own Gilded Age, inequality moves in cycles. The future looks like a rough ride. Aeon magazine. https://aeon.co/essays/history-tells-us-where-the-wealth-gap-leads

Wilkinson, R. G., & Pickett, K. E. (2009). The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger. New York, NY, USA: Bloomsbury USA.

Wilkinson, R.G., & Pickett, K.E. (2017). The Science Is In: Greater Equality Makes Societies Healthier and Richer. Evonomics https://evonomics.com/wilkinson-pickett-income-inequality-fix-economy/

Yu, Z., & Wang, F. (2017). Income inequality and happiness: An inverted U-shaped curve. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(NOV), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02052