Fast and Slow Thinking

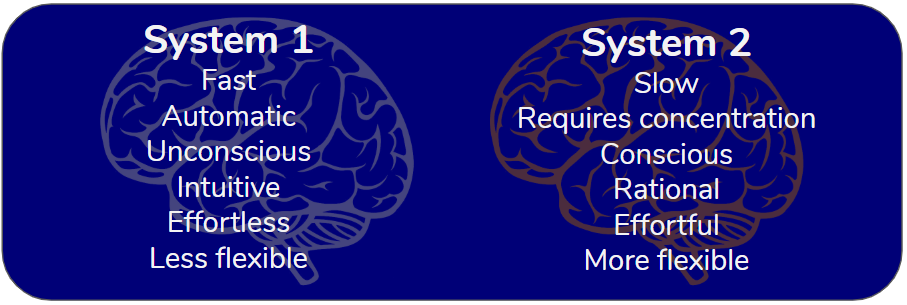

As we look more closely at our perception and thinking, we find that some of it is quite automatic and effortless. Other situations require our conscious concentration and make us tired very quickly. So solving the equation “2 + 2” feels quite differently to us from solving the equation “17 * 23”.

In psychology, these different processes are often roughly divided into two ways of thinking – a fast System 1, and a slow System 2. We often think our System 2 is in control; in fact, System 1 dominates our perception, thinking and acting. Because System 1 helps us to navigate quickly and effortlessly and survive in a complex, dynamic world.

The Israeli-American psychologist Daniel Kahneman has popularized the insights about System 1 and System 2 in in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, published in 2011.

Fast thinking or slow thinking

In this lesson students sort their own experience of thinking into fast and slow processes. Based on this, they come to understand that our thinking is shaped through experience such that things we do often and regularly become easier over time.

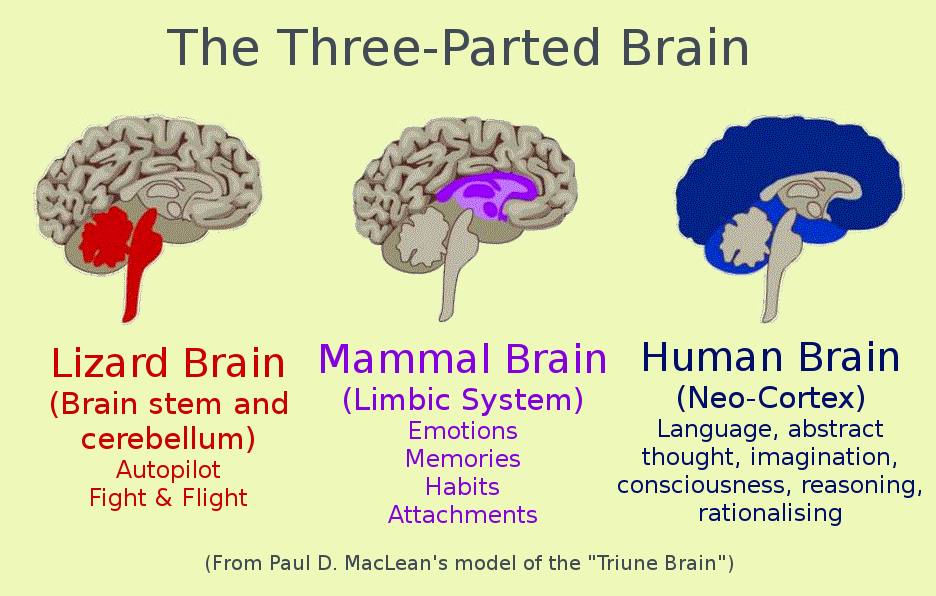

Reading text – brain areas and their functions

A handout about the “Triune Brain” model highlighting different functions of different brain regions

Why fast thinking?

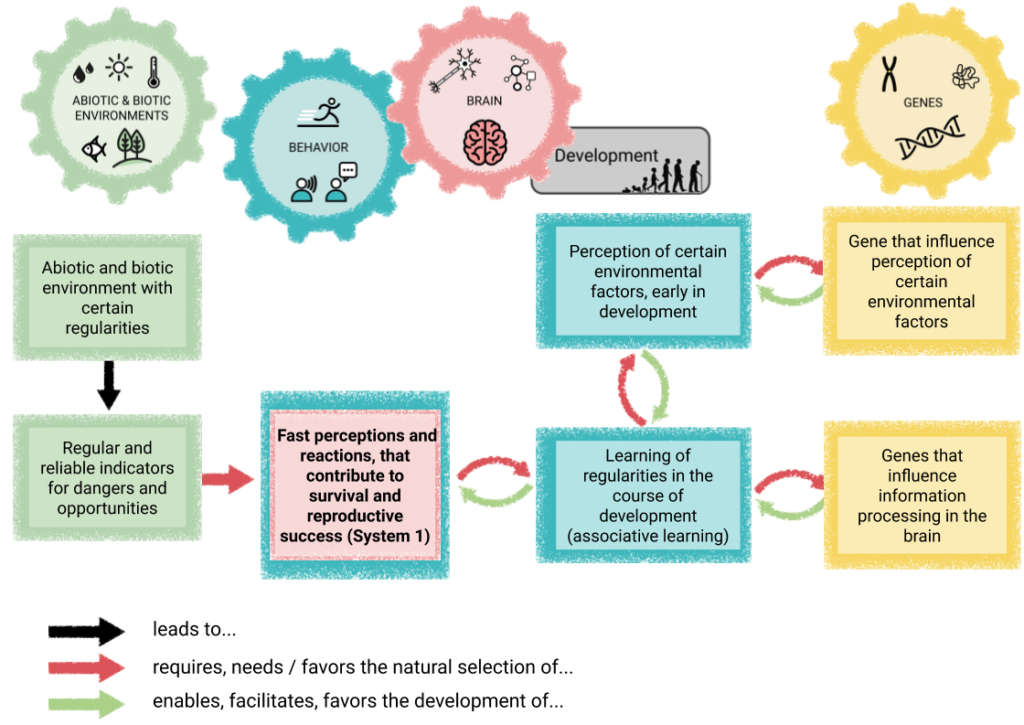

We have many of the mental activities of “System 1” in common with other species of animals, and we are born with some of these abilities. Other intuitions are also developed in the course of our life through repeated experience of stimuli and practice. That’s why we can barely suppress reading words in our mother tongue or solving “2 + 2”, even though there was a time when this was new and hard work for us.

The function of these unconscious and automatic intuitions, for us and other animals, is to quickly learn the regularities of our social and natural environment, to perceive them quickly and without much energy expenditure, and to respond to them rapidly. System 1 enables us to navigate and survive in a complex, dynamic world, but it does not always provide a factually accurate view. Simplified or distorted perceptions of the world have become part of how humans think because they may have no negative effects, and often positive effects for us. So we can not prevent that sometimes we see faces where there are none, or get “tricked” by other optical illusions. All we can do is learn when System 1 distorts and simplifies our perception of the world, and not always blindly trust our perception.

We can also change many processes of System 1 over time by using System 2 and a lot of practice. So we humans, if we want, can become all sorts of experts!

“The capabilities of System 1 include innate skills that we share with other animals. We are born prepared to perceive the world around us, recognize objects, orient attention, avoid losses, and fear spiders. Other mental activities become fast and automatic through prolonged practice.”

Daniel Kahneman (2011)

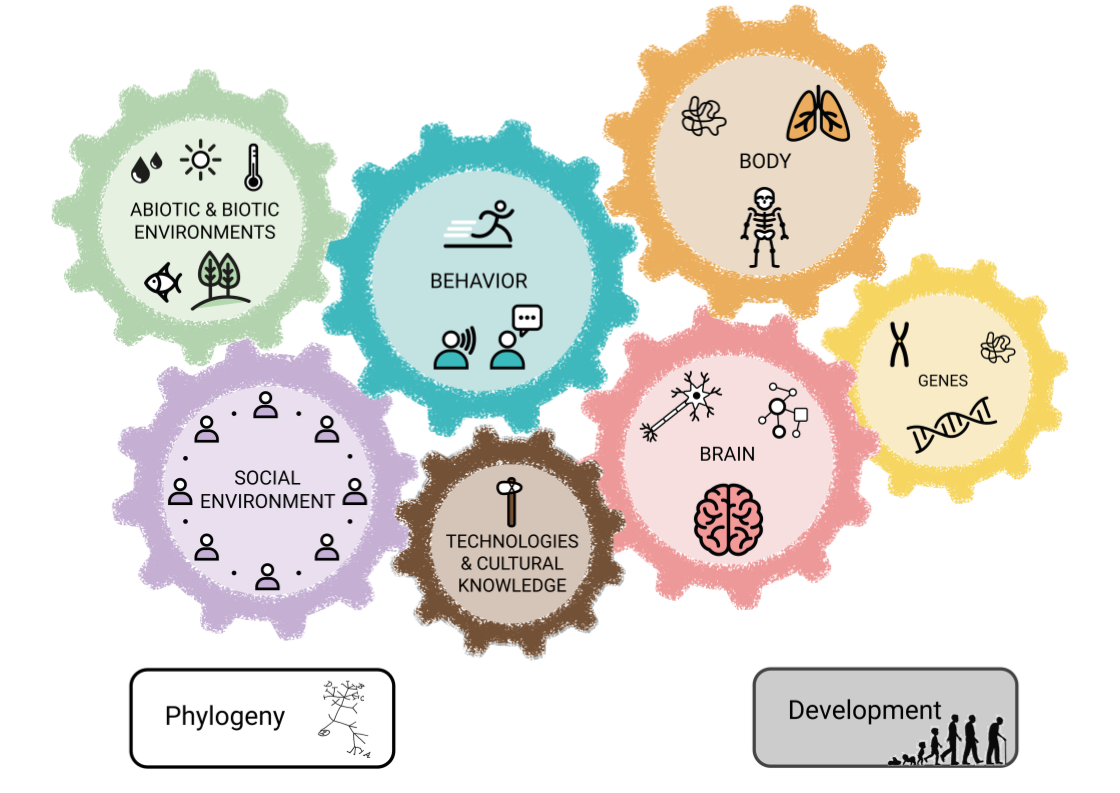

Causal Map: Fast Thinking (System 1)

The evolution of System 1 began early in the evolution of life with the ability for associative learning.

Causal maps on the evolution of human traits

All causal maps on human evolution in one Google slide file

Fast Thinking and "cognitive biases"

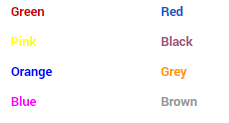

Fast thinking leads to a distorted or simplified perception of reality. Unfortunately, by definition, we can not see most of these processes because they are unconscious. But optical illusions allow us to watch our fast thinking “at work”. In doing so, we can reflect on why these automatic distortions are taking place at all – do they have a function? Do they allow us (and did they allow our ancestors) to cope with the environment, or are they useless “software bugs” in our brains?

The chessboard illusion. Square A and B are the same shade of grey. Image source: Edward H. Adelson. CC BY-SA 4.0

For navigating around the world, it is more helpful to perceive light-dark contrasts than absolute color tones.

Picture of a mountain range on Mars. We involuntarily recognize a face. Image source.

To navigate around the world, it is helpful to quickly recognize the presence of other living things (such as predators!) and other humans. It was better for our ancestors to be on the safe side: seeing no face where there is one can be deadly!

“Kanizsa Triangle” – We “complete” the picture and see lines where there are none. Image source.

For navigating around the world, it helps to turn even sparse information into meaningful information, regular and familiar patterns.

However, this distortion and simplification of reality happens not only when looking at optical illusions, but almost always!

For the many pieces of information that ceaselessly enter our brains through our senses must in some way first be rated “important,” “meaningful,” “similar,” or “new.” So our brain constantly filters, simplifies, categorizes, interprets and evaluates this information, usually without us being aware of it: Is that a dangerous animal? Can I ignore that? Am I sure enough? Has this situation happened before? etc.

These processes of “fast thinking” have were selected during our evolutionary history, allowing our ancestors to navigate a complex world and act fast. They therefore fulfill vital functions. It would be impossible for us to move and survive if, instead, we had to perform all of these automatic processes through concentrated, slow, rational thinking.

Usually these automatic simplifications of reality are helpful or at least harmless – we humans easily recognize faces everywhere, even where there are none. But these cognitive distortions can also lead to misinterpretations, prejudices, false accusations, and thus to social conflicts and other negative consequences for ourselves, our social environment, and our society.

Awareness of how our brain constantly and automatically filters and evaluates reality is a first step in defusing the potentially negative impact of cognitive biases on our actions and in fostering critical thinking.

Function of cognitive biases

In this lesson students learn about the concept of cognitive biases as well as a number of important cognitive biases that may affect our well-being and social interactions, identify their causes in evolutionary history, their functions, and reflect on how to cope with cognitive biases.

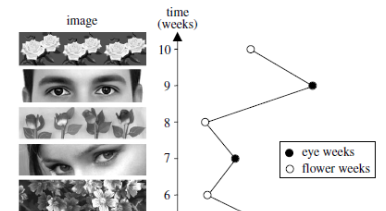

Perception of eyes and prosocial behavior

A behavioral experiment that tells us about the role of unconscious perception, particularly the perception of human eyes, on human social behavior.

Why slow thinking?

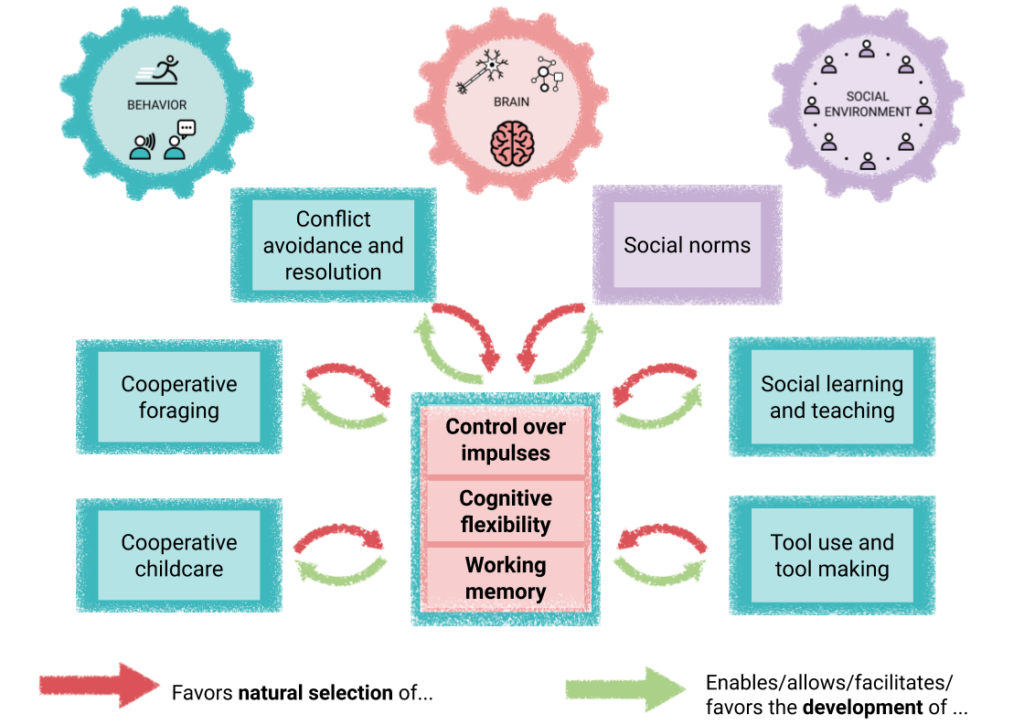

The mental processes of System 1 and System 2 are not strictly separable – many processes are more or less automatic, more or less conscious, more or less flexible depending on many factors. Other species, e.g. primates, may have certain “slow thinking” skills. Nevertheless, the activities of System 2 seem to be particularly pronounced in us humans. They probably originated throughout our evolutionary history because certain mental abilities, such as controlling emotional impulses in social situations, focusing on activities such as learning and teaching the use and manufacture of complex tools, and coordination of body movements, have become increasingly important to the survival of our ancestors.

System 2 is related to the activity of the cerebral cortex and we do not come into the world with it – it develops throughout our lives.

We often think that our System 2 (our ‘self’, our ‘intention’, our ‘will’) is in control, after all we are mostly only aware of System 2. In fact, System 1 generally dominates our perception, our thinking and acting, in part because System 2 consumes a lot of energy and is exhausting!

Observe how often and in what situations you and your mind use System 1 and System 2 thinking over the course of a day.

“The operations of System 2 are often associated with the subjective experience of agency, choice, and concentration. (...) When we think of ourselves, we identify with System 2, the conscious, reasoning self that has beliefs, makes choices, and decides what to think about and what to do.”

Daniel Kahneman (2011)

Causal Map: Slow Thinking (System 2)

The survival and reproduction of our ancestors increasingly depended on various cognitive and social abilities. Cooperative foraging and child care, the learning and teaching of toolmaking and other complex knowledge, the avoidance and resolution of conflicts in group life increasingly required individuals to be able to control their emotional impulses, focus on something even when it becomes difficult, flexibly change their strategy and attention, and keep several things in mind at the same time.

Riding a bike is a complex task, but once we have mastered it, we do it pretty easily – what once was System 2 thinking, becomes System 1. But then our brain will make it really difficult for us to ride a bike that functions differently.

What roles do System 1 and System 2 have in allowing us to learn and “unlearn” different things throughout our lives?

Backwards Brain Bicycle

This video is about a bicycle that works differently than normal bicycles, and how challenging it is for our minds to learn how to ride this new bicycle.

Carol Dweck talks about “Growth Mindset.” Growth mindset (as opposed to “fixed mindset”) stands for the belief or attitude that certain qualities and abilities of a person are not fixed or innate, but that one can continuously improve one’s own abilities through learning from mistakes, experience, and effort. These mindsets in turn have a strong impact on our motivation and thus become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The metaphors of fast thinking and slow thinking can help us to understand why it is often difficult and hard work to learn new things.

According to Carol Dweck, promoting a growth mindset in students is an important task of school education.

“Whether you think you can, or you think you can’t—you’re right.”

– Henry Ford

References

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.