Symbols and Language

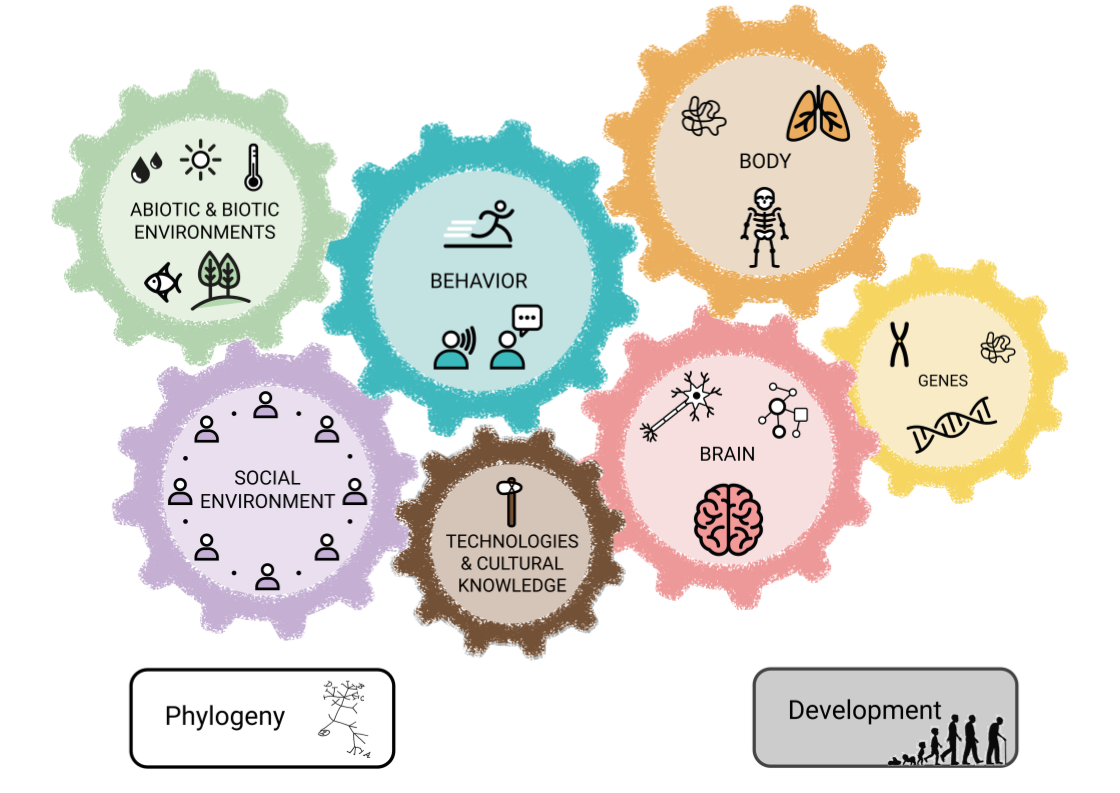

Human language and our capacity for symbolic thinking are probably among the most challenging set of human traits to study and understand. Scientists studying these traits have to ask a number of inter-related questions:

- How does our capacity for symbolic thinking and communication compare to the abilities of other animals?

- When in our evolutionary history did those traits emerge?

- Why and how do these abilities develop during our lifetime?

- How do they affect our everyday experience and behaviors?

At the same time, they comprise an important set of traits seemingly unique to our species’ behavior, essential for cultural evolution, and for our ability to live and cooperate with millions of people. Signs of wide-spread symbol use in archaeological findings are considered to be a hallmark of the emergence of “behaviorally modern” humans.

One reason that it may be difficult for us to understand the nature of human language (whether it is spoken words, sign language, writing, or any other form of human symbolic communication), compared to the communication in other animals, it that it is so much part of our own personal experience and identity that it is difficult to imagine what our lives and experiences would be like without these capacities.

Can other animals learn human language?

The longest “sentence”, that was supposedly ever uttered by a non-human ape:

“Give orange me give eat orange me eat orange give me eat orange give me you.”

– Nim Chimpsky

How does it differ from the kinds of communication we humans engage in with our language? What aspects are similar? What aspects are missing?

"We see that the other primates have complex social lives, but that they do it without languages. They do have many ways to communicate, but none of them are as information-rich and temporally complex as language. Even humans who cannot speak can still use language (sign language or writing).

To understand how important this is, try to go a few hours using words that represent only things in your immediate line of sight, that refer only to the present moment, and that contain no adjectives or representations of your inner thoughts. It will not be easy. We take the importance of language for granted because we are so totally reliant on it."

Agustín Fuentes (2018, p. 151)

Although scientists have been able to teach apes to use a wide range of symbols, it takes a very long time and many trials for apes to learn each one, and they can learn up to a few hundred to a thousand signs this way. In contrast, human children at the age of 2 or 3 have already picked up words in rapid speed simply by interacting with other humans around them, learning between 10 and 20 words per week. Compared to small children, chimpanzees and other apes do not even seem to understand simple pointing gestures that we humans use to communicate and point out to each other interesting things in the world. This simple human capacity represents an important element that allows children to learn and allows adults to teach them a large array of words for things in everyday interactions.

Humans also use language to ask each other questions, tell each other things, such as what happened to them earlier and what they plan to do later, what they feel and think. Apes do not seem to use their learned signs to communicate in this way, they mainly seem to use it to request things in their immediate environment (like “Give me orange”).

What seems to be another important and unique aspect of language is that humans can combine words, in virtually endless combinations, into meaningful sentences, simply by following the rules of grammar. Scientists call this aspect of human language “generativity” – meaning that we can use it to communicate an infinite number of ideas by combining sounds and words in different and novel ways. Every day, you may come across sentences that you have never heard or read before (like possibly the sentences in this paragraph), and yet you will mostly understand what they mean. Non-human animal communication does not seem to possess this capacity, or only in very rudimentary form.

Symbols and symbolic thinking

Another particularly important aspect of human language is its use of symbols. The word symbol comes from the greek symbolon which means a token or something that indicates that something is real or genuine.

Symbols have their meaning based on some relation to something else. These relations are learned and taught, such that everyone in a symbolic community knows what the symbol means or refers to. Symbols can have more or less arbitrary relations to the thing that they stand for. For example, an image of an eye stands for a real eye and is not very arbitrary, it shares actual features of an eye, it looks like an eye, so every human in the world will know that it stands for an eye – such pictures that represent real things in the world are also called icons.

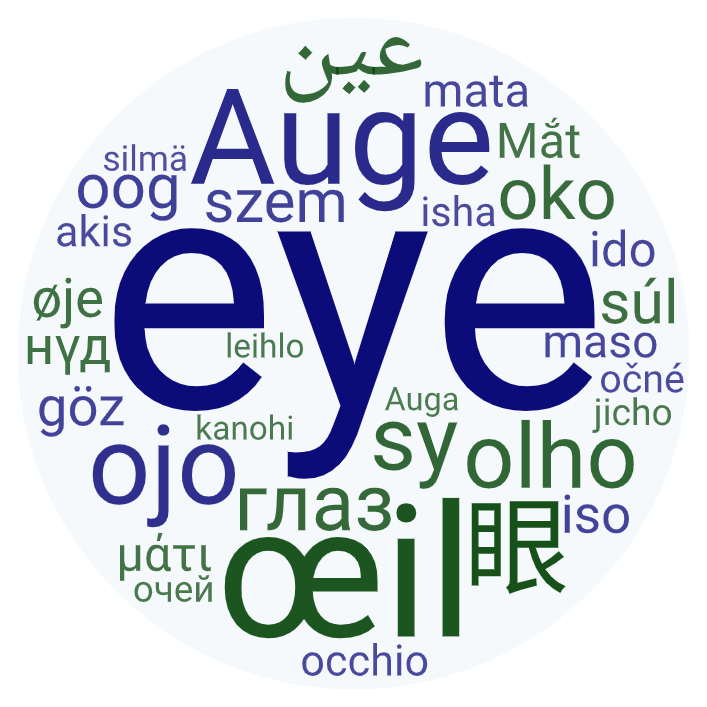

But the word “eye” in letters or sounds is quite an arbitrary symbol – nobody who hasn’t learned the English language will know what it means. Different languages have different, equally arbitrary words for the same thing. In this way, words are often regarded as truly arbitrary symbols – they have their meaning based on everyone understanding what it stands for, and not at all based on resembling the “real” thing.

Similarly, some gestures in sign languages are more or less iconic – mimicking the real thing such that someone who hasn’t learned the sign language can somewhat guess what is meant. Other sign language gestures are rather arbitrary such that one would have to learn the sign language to know what is meant. The Braille writing system for the blind is, like our alphabet, truly arbitrary.

Often, more arbitrary symbols slowly develop over time from less arbitrary icons – think about the evolution of writing systems – from the first pictograms and Egyptian hieroglyphs to the abstract Latin letters and other writing systems in use around the world today.

Words in different languages that stand for an eye. They are all arbitrary symbols, because they have no resemblance to the real thing. People only know what the symbol means if they grew up learning from their social environment what it means. On the other hand – you being told that all of these words mean “eye” allows you to understand what all the words mean even if you have never seen them before – that’s how quickly we can learn the meaning of new symbols.

Through arbitrary symbols, we can also express ideas and abstract concepts, which are not real visible objects and things we can experience with our senses (unlike with icons) – such as the concepts of science, evolution, sustainability, past, future, climate change, cause, effect, heaven, hell, etc.

Scientists studied how symbols influence the ability of children and chimpanzees to control their impulses.

Language and symbolic thinking – a blessing and a curse?

With language and symbols, our species is able to communicate about things beyond our immediate experience, and produce a sense that these absent and abstract things are “in front of our eyes”. It is as if the thing that we are expressing with the help of words or other symbols, is really there in front of us. This is great for motivating us to plan and prepare for tomorrow’s hunt (or exam), for reminding us of the danger or unpleasant situation we faced earlier so we can learn from it, for telling others about what we have experienced so that they might learn from it, or to build a sense of belonging and common identity by sharing our thoughts, feelings and experiences with others.

But this ability also has a dark side – with the help of symbolic language we can also make absent or abstract things appear “true” and “real” which are negative or scary to us. The danger or unpleasant situation we faced earlier is not really there anymore right now, and we can create interpretations and judgments of ourselves, others, and the world around us which are not helpful to our goals, do not motivate us to act in helpful ways, or can be even harmful to ourselves or those we care about.

Thus, our ability for language, by creating an almost endless stream of thoughts in our head, together with our ability for mental time travel, allowing us to remember and relive the past and imagine futures, seems to make us vulnerable to a number of mental health problems, as well as social conflict.

In this way, one of the more important reasons for learning about human language and symbolic thinking might be to cultivate the competency to use language, symbols, and symbolic thinking more flexibly, and in ways that are less harmful. One way to reduce these negative effects of language and symbols is to become more aware of the fact that the thoughts, images and memories created in our mind are not “the real thing”, to look at and listen to them more like you would listen to the radio, to hold them a bit more lightly. Some behavioral scientists use the word “defusion” for this ability, which means that we can notice our inner language but still distance ourselves from the content of our thoughts, rather than being totally “fused” with it.

"Although we humans have gained the ability to extract ourselves from the physical jungle, through language we are now recreating the danger of the jungle in our heads again and again."

Ciarrocchi & Hayes (2018, p. 118)

"Imagine if we could teach young people to become mindful of the ways that symbols can dominate our interpretations of experience and can become unhelpful. They might then learn to use symbols like tools, and “put them down” when no longer useful. They might become less caught up in self-criticism, materialism and prejudice. Could they pass these lessons on to their children?”

Ciarrocchi & Hayes (2018, p. 121)

Psychologist Russ Harris explains the metaphor of a radio station for our constant stream of (often negative) thoughts.

Language and the development of our perception

What is the connection between language and the development of our perception? Is language just a way of expressing our existing perceptions, thoughts, ideas and feelings? Or does language also influence what we think and feel, or how we perceive the world, in the course of our lives?

If the latter is true, namely that language influences our perception, then people who speak different languages would have to perceive their world in significantly different ways.

Research by psychologists suggests that this is indeed the case – for example, people from different language communities seem to perceive time and space, colors, even emotions and sensations differently, based on the kinds of words that are used in their language to categorize the world around them.

Nonetheless, there also seems to be some similarity or stability across languages – so the cultural evolution of language is both shaping our perception but is also shaped by the commonalities of our basic human physiology and by how we perceive the physical world.

How language shapes the way we think

Cognitive scientist Lera Boroditsky talks about the debate around the relation between language and perception, and scientific insights into how language shapes our perceptions and interpretations of the world.

Language and Emotion

With the help of language we also express our emotions. As with other perceptions, the concepts we call emotions are also partly stemming from the physiological reality of our body (i.e. words for emotions emerge, in part, to reflect various physiological states our bodies have evolved in order to react in different situations), but the words we use to express these states can also take on a much more complex and abstract meaning, such that we not only sense but also interpret and evaluate these states.

This aspect leads to scientists debating whether the way we experience certain emotions is really the same as what other animals experience. Due to our common evolutionary heritage, we share with animals many physiological functions that underpin our sensation of emotions in our body, such as the stress response and the production of hormones such as serotonin, dopamine, cortisol, adrenaline and oxytocin. However, because of language, the way we humans experience emotions may be much more complex and fine-grained, leading to more and more abstract ideas about what emotions are, and leading to many more different emotional concepts – all tied up with our ever growing collection of memories and stories about who we are as individuals within our communities. Think about what you associate with the words “joy”, “excitement”, “melancholy”, “stress”, or “guilt” – probably more than how these states make you feel in your body, these words perhaps also elicit memories of situations and people, or judgments of these states as good or bad.

As with colors, space, and time, different languages have different words for emotions and they categorize general mental states differently. Nonetheless, all languages seem to categorize our mental states based on a general “Good or Bad” dimension, as well as based on a general dimension of intensity.

Being able to express our emotions with language seems to be important for our ability to regulate our emotions. For example, studies find that the more vocabulary a child knows, the better they are able to regulate their emotions. Just as symbols might allow us to create some “emotional distance” towards something so that we can approach it differently (e.g. with less emotional intensity), having words for emotions can help us to make sense of our experience and share this experience with others, which can in turn help us to regulate our mental states. Being able to express our experiences with language is also important for building a connection and shared identity with other people, a key to our species’ ability to work together for the common good.

On the other hand, since emotion words are often tied to evaluations and interpretations such as “this is good, I want more of this”, or “this is bad, I don’t like this, I want this to go away”, we might also get too caught up in evaluating all the things that are ongoing in our body. For example, instead of just noticing a slight tinge of anxiety in the chest or stomach and let it pass, we might get caught up in interpreting it, finding the cause of it, making predictions about it, going through memories related to it, generally evaluating this sensation, which in turn might lead to more of such sensations and so on. Instead of noticing that we are currently under some stress, we might get caught up in interpreting the situation as more or less terrible and hopeless, or not. In fact, research has found that our interpretations of mental states like stress can be more important in how they affect our health and well-being than the actual states themselves.

see also: Emotions

Two articles about the research on how emotion words and concepts differ across cultures:

Our everyday experience is so diverse that we may experience things for which we have no words, and maybe no language has a word – and yet we experience them.

A fun project is to “invent” words to map onto glimpses of our diverse experiences in life – and to thus make us aware that we share these with other people.

In this Ted talk, the creator of the “Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows” gives us interesting insights into the meaning and importance of words, based on his experience of inventing new words and people’s reactions to them.

Classroom ideas:

-

Students search for their favorite words in the Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows (see website and youtube channel links above) that express an important or meaningful experience to them and that they would want to be used by people, and write a paragraph about why the word and its meaning is important to them.

-

Students invent their own words for an emotion or experience that they would like to see expressed in language, and write a dictionary entry for it. Students can use elements of languages that they know to create these words – prefixes, suffixes, word stems etc.

One interesting way that scientists try to understand the link between language and emotion is to compare how humans react to emotional words or make emotional decisions in their mother tongue vs. a second language.

The results tell us something about how we create meaning as we learn a language throughout our development in interactions with our parents and other humans – emotional words, swear words or norms in our mother tongue tend to be more “real” to us and tend to arouse more emotional reactions than the same words in a second language, which we learned later in life and through different ways than learning a mother tongue.

Early evolution of language and symbolic thinking

It is very difficult for anthropologists to find a precise time for when human language emerged, because this trait leaves no traces and the capacity for language may come in different forms and involves a diversity of related traits (from bodily traits that enable language production, to artifacts that may represent our ancestor’s capacity for language).

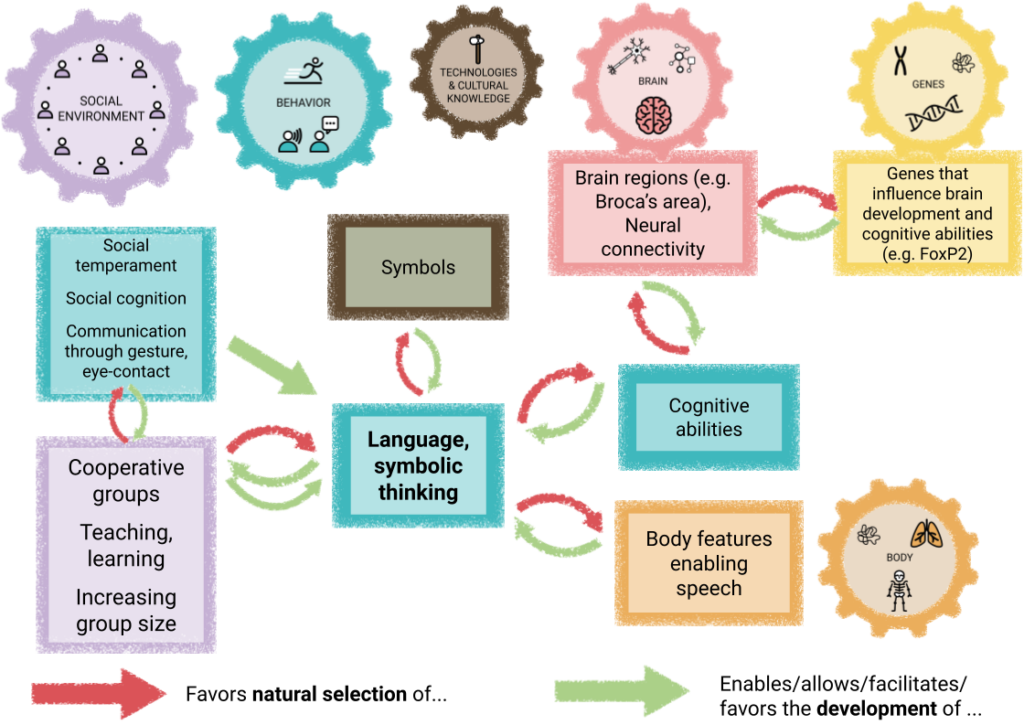

But many think that human language could only evolve in the first place because of the evolution of cooperation in our species. Exchanging information through language is essentially a cooperative act – members of a group share helpful information with each other. If there was mostly competition between individuals, or if survival did not depend as strongly on cooperating and coordinating with others in the group, there would not be a strong motivation and selection pressure for regularly exchanging helpful information with others, and their would be no benefit in having traits that allow the efficient and effective exchange of such information.

Therefore, major prerequisites for the development of human language were an enhanced social tolerance, the enhanced ability (and motivation) for sharing information through gesture (e.g. pointing) and eye-contact, and thus the ability to created a shared attention (i.e. we know that we are looking at the same thing). All these traits have been selected in the course of human evolution because of a need to cooperate, coordinate, and teach and learn complex skills.

Many think that communication through gesture must have come before speech. Through the pointing gesture one can refer specifically to something in the environment, and gestures that imitate something are more iconic (see above), that is – such gestures refer to or mimic concrete real-world entities (i.e. they are non-arbitrary). Whereas with sounds it would not be obvious to others what the sound is supposed to refer to (i.e. words are most often arbitrary in relation to what they refer to). Furthermore, the teaching of more and more complex skills created strong selection pressure for using communication, that is, as ancestral communities became dependent on tools for survival, they therefore became dependent on teaching each other how to make these tools – those groups with better abilities to teach and learn from each other would out compete groups with lesser skill. This probably started with gestures (pointing, body movements) and eye gaze towards relevant objects, and eventually may have been combined with sounds in order to have the hands free. Even sounds that indicate “here”, “there”, “like this”, “You”, “I”, “No”, “Yes” would be advantageous. Through regular cooperative interactions among individuals, it would become clear what is meant by the sounds. Eventually, the meaning of the sounds would be understood without the gesture – the sounds would become arbitrary – that means any sound could have a specific meaning for these particular communicating individuals, just because they all knew and learned what it meant.

It also seems that the making of complex tools (especially tools that require a lot of different steps to make or that are made up of several parts, such as spears) requires similar cognitive abilities as the ability for language. Making these tools requires an ability to organize and plan actions in many hierarchical steps and sequences. This is similar to how human languages are structured through grammar – understanding this sentence requires the ability to have all the parts of the sentence in your mind and to combine them in the right way to understand the meaning. Scientists have found a gene, FOXP2, that seems to be involved in those cognitive functions, and people who have a mutation in this gene seem to have impaired language abilities. Making tools also requires strong control and coordination of body movements. and this is similar to how producing speech requires strong control of breath, tongue and lips.

The expansion of the brain, particularly the neocortex, changes in neuronal activity and connectivity, and increasing lateralization of brain function during human evolution, also seem to be responsible for our capacity for learning language and symbolic relationships so effortlessly and quickly, as well as for the capacity for “offline thinking” – that is our ability to create endless streams of thought that are not directly connected to our senses and experience in the here-and-now. Broca’s area is a region of the cortex that has been linked to the processing of language, gestures, and symbols.

Furthermore, there are anatomical features of humans that allow us to produce a wide range of vowels and consonants that human spoken languages are made of. Some scientists suggest that even the changes of our body that resulted from an adaptation to upright walking, enabled us to produce a greater variety of sounds compared to chimpanzees. The vocal tract of Homo sapiens has undergone further changes compared to that of our earlier ancestors and relatives, and might also have been adaptations to articulate speech.

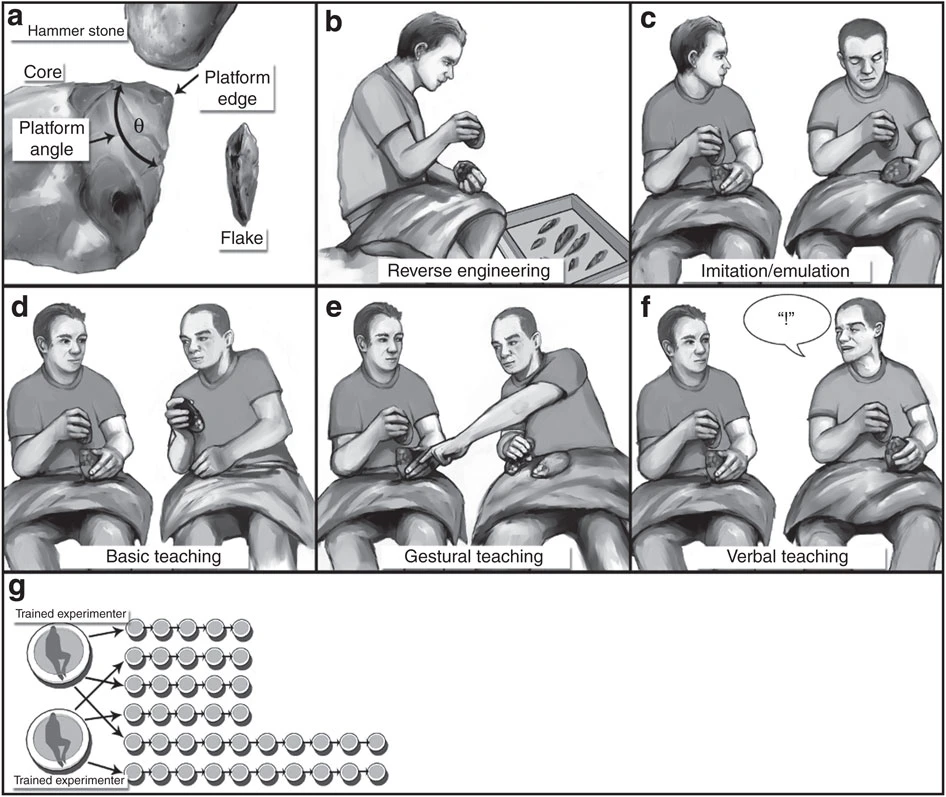

Experiments have found that humans can teach and learn from others how to make stone tools much faster and more accurately if they are able to use gesture, and especially if they are able to use gesture plus spoken language, compared to just observing someone.

Experiment on the the co-evolution of tool making, teaching, and language

An experiment in which researchers wanted to examine the role of teaching and communication in the transmission of toolmaking.

Symbol use embedded within physical artifacts is considered one of the hallmarks of behaviorally modern humans – humans who not only resemble us in their anatomy but also in their behavior. So anthropologists, archaeologists and cognitive scientists are particularly interested in signs of the regular use of symbols in archaeological findings.

Some anthropologists consider how even the regular making and use of stone tools could have served as early symbols – stone tools, especially when they are carried around and used over and over again over long periods of time, could start to carry a meaning beyond the mere stones that they are – they possibly started to symbolize things, or re-mind the early humans of ideas like “the successful hunting trip we had earlier over there” , “I am a good tool maker”, “I am a good guy to go hunting with”, or “I am prepared”. The presence of these tools might also have affected our ability for mental time travel – reminding us of events in the past and helping us anticipate events in the future.

However, archaeologists are especially interested in looking for things that do not seem to have an obvious function, other than their use as symbol. For example, signs that pigments are used, or that early humans made markings on objects, or used objects as personal ornaments – these are signs that the things had some meanings for a community of people.

Findings of shell beads that are estimated to be more than 80 000 years old lead scientists to think that by this time, these humans had an advanced system of symbols that shaped their behaviors and social lives. Furthermore, these humans must have had spoken language in order to be able to transmit the meaning of the symbols. But these behaviors and the social and cognitive abilities underlying them probably emerged over a long period of time before that, through the interaction of humans and the gradual accumulation and transmission of a cultural world full of symbols.

What might these beads have meant to others in the community about the person wearing them?

Etchings on an ocre plate of the Blombos cave in South-Africa, ca. 77,000–75,000 years old. Image source: Smithsonian Institution

What did these etchings symbolize? What meaning did they carry for the people? The meanings seem arbitrary – it is not clear to anyone outside the community what they mean – only people who grow up learning about the meaning.

What excavated beads tell us about the when and where of human evolution. The conversation, 2016. http://theconversation.com/what-excavated-beads-tell-us-about-the-when-and-where-of-human-evolution-53695

Causal map for the evolution of language and symbolic thinking

Causal maps on the evolution of human traits

All causal maps on human evolution in one Google slide file

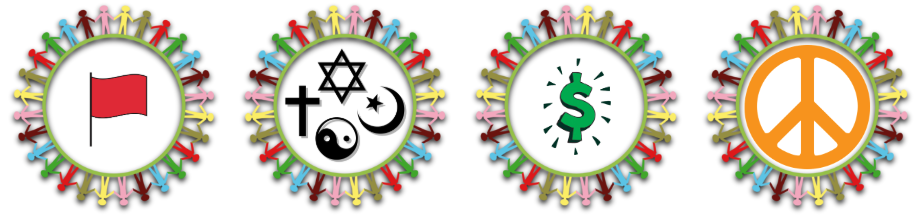

Symbolic Thinking and Cooperation

The ability for language and symbolic thinking had another far-reaching function in the evolutionary history of our species: By using and understanding symbols and stories, many people could build a common identity, even if they would never really get to know each other personally. This has made it possible for us to cooperate with thousands and even millions of people. Especially in the last 10,000–5000 years, with the beginning of agriculture, our group sizes have drastically increased, and with it, our reliance on symbols and language to cultivate group identity has grown more important.

Similarly to how language offers a blessing and curse to our well-being, so also the use of language and symbols provides great benefit for cooperation but has also produced great social conflict and harm.

see also: Life with other groups

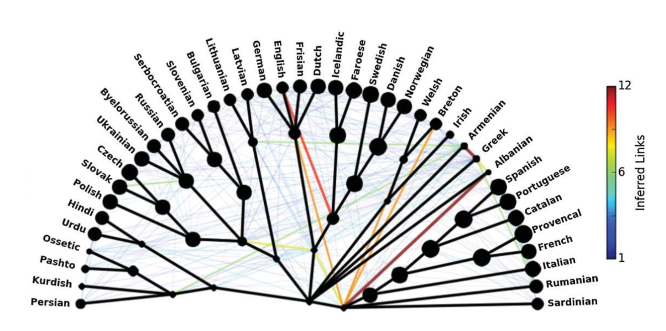

The cultural evolution of language

Similar to how evolutionary biologists examine today’s existing living organisms in order to deduce possible common origins and common ancestry on the basis of their similarities, linguists (from Latin lingua – tongue, language) examine today’s existing languages to determine possible common origins of all human languages or close language families.

This graph represents the phylogenetic history of 40 Indo-European languages, both with the descendance of languages from earlier versions (the black branches and nodes) as is typical in phylogenetic graphs of the biological evolution of species, and with the borrowing of words from other languages (the colored lines linking across branches). Notice, for example, the colored branches linking to today’s English language.

Loanwords are words that have been adopted from another language. This usually happens because there is no word in the own language that would reflect the meaning as well as the loanword. (It is similar to how we like to quote people who said things in a way that we think couldn’t be expressed any better, so we “loan” or “borrow” their words.)

The english language has been influenced by so many other languages, and in the course of history many words were loaned from these languages, e.g. from latin, greek, arabic and french: porc, beef, soup, alcohol, average, art, hour, toilet, chair, paper ….

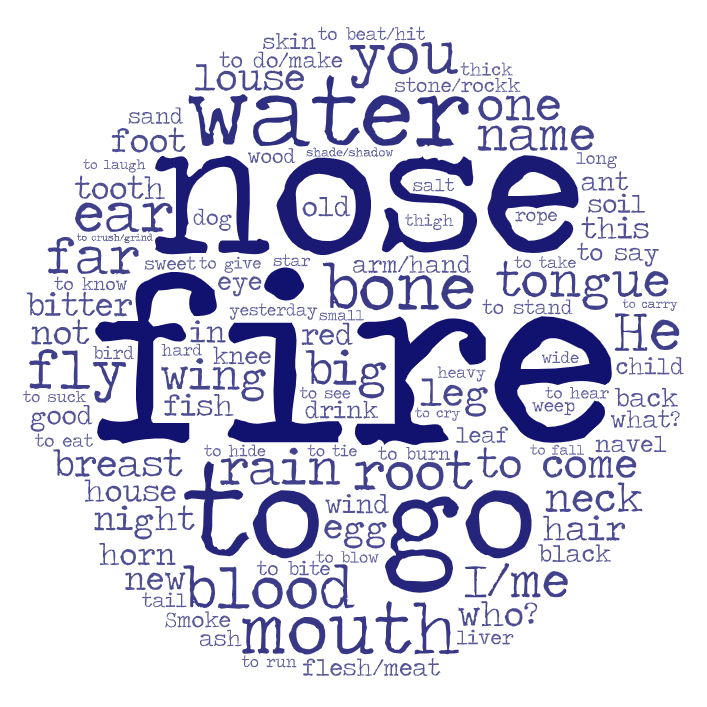

A team of linguists, including researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, has created a list of 100 words for which an original word apparently also exists in 41 of the worlds known languages (the so-called Leipzig-Jakarta list). Linguists say that these words are “resistant to borrowing” – meaning these concepts have not been “loaned” from other languages but were expressed by the speakers of each language since early on in the emergnce of the language.

What could this list tell us about the life and experience of our early ancestors that began to speak the early human languages?

References

Cataldo, D. M., Migliano, A. B., & Vinicius, L. (2018). Speech, stone tool-making and the evolution of language. PLoS ONE, 13(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191071

Ciarrochi, J. & Hayes, L. (2018). Shaping DNA (Discoverer, Noticer, and Advisor): A Contextual Behavioral Science Approach to Youth Intervention. In: Wilson, D.S. & Hayes, S.C. Evolution and Contextual Behavioral Science (pp. 107-124). Context Press.

Colombetti, G. (2009). What language does to feelings. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 16, 4–26. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7bfe/6bb7375f1b06d13f90f2044b2eebef94765c.pdf

Fuentes, A. (2018). Biological Anthropology: Concepts and Connections (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

Hayes, S. C., & Sanford, B. T. (2014). Cooperation came first: Evolution and human cognition. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 101(1), 112–129. https://doi.org/10.1002/jeab.64

Jablonka, E., Ginsburg, S., & Dor, D. (2012). The co-evolution of language and emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 367(1599), 2152–2159. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2012.0117

Jackson, J. C., Watts, J., Henry, T. R., List, J.-M., Forkel, R., Mucha, P. J., … Lindquist, K. A. (2019). Emotion semantics show both cultural variation and universal structure. Science, 1522(December), 1517–1522. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw8160

Jeffares, B. (2010). The co-evolution of tools and minds: Cognition and material culture in the hominin lineage. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 9(4), 503–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-010-9176-9

Kay, P., & Regier, T. (2006). Language, thought and color: recent developments. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(2), 51–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2005.12.007

Kuhn, S. L., & Stiner, M. C. (2007). Paleolithic ornaments: Implications for cognition, demography and identity. Diogenes, 54(2), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0392192107076870

Laland, K. N. (2017). The origins of language in teaching. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 24(1), 225–231. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-016-1077-7

List, J.-M., Nelson-Sathi, S., Geisler, H., & Martin, W. (2014). Networks of lexical borrowing and lateral gene transfer in language and genome evolution. BioEssays, 36(2), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.201300096

Monestès, J. L. (2015). A Functional Place for Language in Evolution: The Contribution of Contextual Behavioral Science to the Study of Human Evolution. The Wiley Handbook of Contextual Behavioral Science, 100-114.

Morgan, T. J. H., Uomini, N. T., Rendell, L. E., Chouinard-Thuly, L., Street, S. E., Lewis, H. M., … Laland, K. N. (2015). Experimental evidence for the co-evolution of hominin tool-making teaching and language. Nature Communications, 6, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7029

Osvath, M., & Gärdenfors, P. (2005). Oldowan Culture and the Evolution of Anticipatory Cognition. Lund University Cognitive Studies, 122, 1–16.

Sterelny, K. (2011). From hominins to humans: how sapiens became behaviourally modern. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 366(1566), 809–822. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0301

Sterelny, K. (2012). Language, gesture, skill: The co-evolutionary foundations of language. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 367(1599), 2141–2151. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2012.0116

Stout, D., & Chaminade, T. (2012). Stone tools, language and the brain in human evolution. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 367(1585), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2011.0099

Tadmor, U., Haspelmath, M., & Taylor, B. (2010). Borrowability and the notion of basic vocabulary. Diachronica. International Journal for Historical Linguistics., 27(2), 226–246. https://doi.org/10.1075/dia.27.2.04tad

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Dictionary_of_Obscure_Sorrows

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lists_of_English_words_by_country_or_language_of_origin