Behaviors of our mind

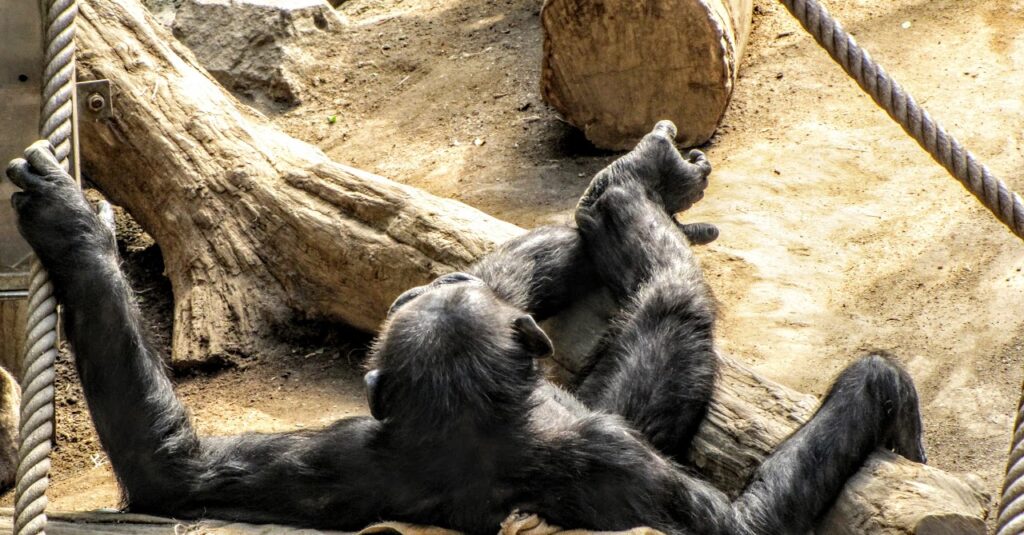

We can pretty easily explain the evolution of traits such as upright walking, and the differences and similarities with our closest relatives are clearly visible in their behavior and physical features. Chimpanzees sometimes walk upright, e.g. to carry food, and we can well imagine that this behavior has survival and reproduction benefits under savanna-like environmental conditions, and thus can spread through natural selection over many generations in a population.

But mental abilities are harder to compare between humans and other great apes. At the same time, these are questions that often fascinate us the most, expecially when we observe our closest relatives, and wonder – what are they thinking? Do they even think? What is “thinking”? What do they feel? What is important to them? Are they worried about the future, do they have hopes? Do they communicate with their conspecifics the way we humans communicate with each other? Are they talking about yesterday and tomorrow, complaining about the behavior of group members, wondering about us humans, making plans, exchanging their experiences, ideas, feelings?

We can not see the behavior that happens in the brain from the outside (researchers consider mental processes such as thinking and feeling also as “behavior”, i.e., something that the body does, only that we can not see it from the outside). Through language and other symbols, we humans can tell each other about our inner experience. But how can we then find out what other animals think and feel, and whether they have similar thoughts or ideas, as we humans do?

Using modern research methods, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), we can at least observe the activity of nerve cells in the brain while organisms do certain things – which brain regions are active how strongly, how are they interconnected? And how does brain activity differ between humans and other species while they are doing similar things?

Another method that scientists use to compare the mental faculties of humans and other species is to observe behaviors while performing certain tasks. If, for example, chimpanzees or small children can remember something from yesterday or think about tomorrow, then they would need to be able to solve a particular task that requires that mental ability – e.g. pick up a tool or save food for later, because they may need it then.

However, we can also easily observe and “explore” our own minds without much effort or fancy technology: what different things does our mind actually do? And why does it do these different things? Which of these different things do we share with other animals, and which not? With which do we come into the world, and which only develop in the course of our life?

Scientists have come up with various metaphors and analogies to describe and differentiate the different behaviors in our mind. For example,

The behaviors of our mind are not always helpful

While all of these behaviors or characters in our mind have important functions and help us act in ways that are important for our survival and well-being, sometimes they are not very useful. For example:

- Fast thinking can give us distorted information that is not helpful to us or leads to social conflict.

- Mental time travel can make us experience negative experiences from the past over and over again, and can make us worry too much about the (imagined) future. It can affect our well-being and behavior in the here-and-now in ways that are not helpful.

- The advisor (the inner voice) can give us too much useless advice or too many negative evaluations (about ourselves, our life, other people, our circumstances), and it can drown out or restrict our Noticers and Discoverers (that is, our ability and motivation to notice the here-and-now and try out new things). It can affect our well-being and behavior in the here-and-now in ways that are not helpful.

“Although we humans have gained the ability to extract ourselves from the physical jungle, through language we are now recreating the danger of the jungle in our heads again and again.”

Ciarrocchi & Hayes (2018, p. 118)

"I've lived through some terrible things in my life, some of which actually happened.”

Mark Twain

A short film about the function and evolution of the human mind.

Possible discussion questions:

- Which of the different behaviors of our mind explored above do you recognize in this video? (slow thinking, fast thinking, mental time travel, noticer, discoverer, advisor)

- What functions do these processes of our mind fulfill? What was their adaptive value in the course of our evolutionary history?

- Why can these adaptations lead to problems for human well-being under today’s (social) environmental conditions?

- What possibilities do you see for mitigating these negative consequences? What can one do as an individual? What can / should we do as a society? What can / should education do?exp

Stephen Hayes: The Mental Spider That Claims to Be Us. Huffington Post, 2012.

see also:

Mismatch

Teaching resources and information for learning about the concept of evolutionary mismatch in human behavior and its potential role in sustainable development

Human evolution – Human needs, values, and wellbeing

Classroom resources for exploring (the evolution of) human needs, values, and well-being

Human evolution – Symbols and language

Human language and our capacity for symbolic thinking are probably among the most challenging set of human traits to study and understand …

Human evolution – Emotions

Classroom ideas and resources for exploring the evolution of emotions

References

- Ciarrochi, J & Hayes, L. (2018). Shaping DNA (Discoverer, Noticer, and Advisor): A Contextual Behavioral Science Approach to Youth Intervention. In: Wilson, D.S. & Hayes, S.C. Evolution and Contextual Behavioral Science (S. 107-124). Oakland: Context Press.

- Hayes, L. L., & Ciarrochi, J. (2015). The Thriving Adolescent. Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Positive Psychology to help teens manage emotions, achieve goals, and build connections. Oakland, CA, USA: Context Press.

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Suddendorf, T. (2006). Foresight and Evolution of the Human Mind. Science, 312, 1006–1007. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1129217

- Osvath, M., & Gärdenfors, P. (2005). Oldowan Culture and the Evolution of Anticipatory Cognition. Lund University Cognitive Studies, 122, 1–16.