The OpenEvo Blog

What was Darwin thinking? A Lesson From The Psychology of Evolution

This View of Life: https://thisviewoflife.com/what-was-darwin-thinking-a-lesson-from-the-psychology-of-evolution/

Published On: February 11, 2016

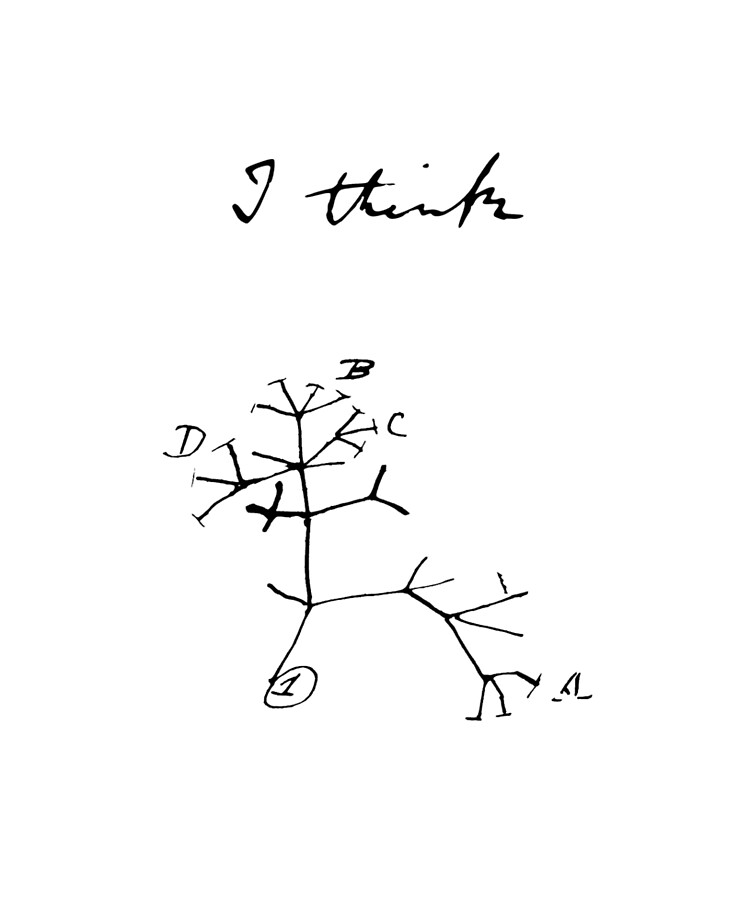

To understand how the theory of evolution has developed, we have to understand what exactly Darwin was thinking. Rather, I should say we have to understand how he was thinking. Evolution is both a set of facts as well as a way of thinking. The facts have no meaning without the theory, just as the theory exists to explain the facts. Charles Darwin’s great talent was to take an expansive array of specific facts about the natural world and distill from them the general principles of evolutionary theory (i.e. variation, selection, and inheritance). These general principles have, in turn, fueled more than a century and a half of scientific discovery.

While readers may have heard of evolutionary psychology, this article is actually about the psychology of evolution itself. That is, the study of how evolutionary thinking develops and thrives across our social species, Charles Darwin being one particularly interesting case study. The psychology of evolution requires conceptualizing the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of evolutionary thinking as a range of behavioral and cognitive traits. The traits of evolutionary thinking may emerge, or not, to varying degrees over the course of human development. These traits exist and further evolve within complex socio-cultural contexts. Many of these traits are already the subjects of study across the human sciences.

Inside Darwin’s Mind

Which traits, biological, psychological, or socio-cultural, allowed Charles Darwin to develop the theory of evolution? We could answer this question from many perspectives. Perhaps Darwin was simply born to be a great scientist? Perhaps it was his travels around the world? Perhaps it was his family of scientific thinkers? Perhaps it was the scientific fervor of his Victorian era culture?

Darwin had clearly developed a single cognitive asset to an extraordinary degree, which is also fundamental to the understanding of evolutionary theory: the human capacity for transfer of learning.

Transfer of learning is the ability to apply your existing knowledge to a new context. It is how the brain builds a coherent network of knowledge by comparing new experiences with prior knowledge, strategically integrating the former with the latter. Darwin excelled at many forms of transfer thinking, perhaps in part because evolution itself is a process of utilizing prior information (genes) to find solutions forever changing (novel) environments. Many of Darwin’s competencies, intellectual as well as social, can be seen in terms of his elaborate mastery of transfer thinking. This is not an obvious conclusion from the simple definition offered just now. Indeed, transfer of learning is a concept in education science notorious for being far more complex than it appears.

Examples of transfer can be extremely simple, even foundational to human cognition. When young children use their knowledge of basic words to understand new sentences and paragraphs, this is a transfer of learning. As children develop their capacity for empathy, this is an example of a transference of their past emotional learning to understand the possible feelings of others around them. More day-to-day examples of transfer can be seen in our ability to work with a diversity of computer operating systems and programs. You are likely able to navigate a wide range of new computer programs and websites because of your intuitive understanding of how software interfaces are designed at a general level. You can transfer your learning from one program to others. All of these basic abilities are based on the human capacity to transfer our learning from prior contexts into novel contexts.

Transfer thinking starts at birth

As for all young humans, transfer thinking started for the baby Charles Darwin on his birthday, February 12, 1809. Human babies, unlike other mammals, don’t do very much for a long time. We are pretty helpless for the first few years (and some might argue, the first few decades) of our lives. Despite this lack of outward skills, babies are born to learn, and, more so, they are born to build an ever-growing network of knowledge about their local world. They build this knowledge network very incrementally. By transferring what they know from past experiences in relation to their new current experiences, babies are constantly refining and growing their foundational social and intellectual capacities. The baby Charles Darwin grew up in a privileged economic and social environment. The fifth of six children, young Charles had ample time to play (and perhaps fight) with his siblings – developing his early social and emotional skills that would eventually transfer to scientific competence as well. As the descendent of wealthy physicians and slave trade abolitionists, young Charles surely had a safe and secure environment. As well, he was embedded in a culture of innovation and reflection. Darwin developed within a social environment filled with role models, amongst family and society, engaged in transferring the best of then current knowledge into new theories and philosophies of the world.

Transfer thinking requires a strong base of organized knowledge

Expectations from Darwin’s family tradition to become a physician ensured he had acquired a strong general education before attending the University of Edinburgh Medical School in 1825. However, medicine and surgery were decidedly not the path for Charles, he had always been more interested in exploring the natural world. By his second year he was studying natural history more than medicine, and spending time in the Plinian Society, a student group focused on asking big picture questions about the nature of science, religion, and society.

Charles was also working for the university museum during this time. Learning taxonomy and classification of the museum’s plant collection, Darwin extended and organized his network of knowledge on the world’s biodiversity. With each new plant he would classify, Darwin would physically place the sample in the appropriate location within the museum taxonomy records. In parallel, Darwin would find the appropriate location within his own mental conception of that particular plant family tree, and and add his new knowledge to that existing network of thought.

Organizing knowledge, such as knowledge about the world’s biodiversity, requires a constant transfer of learning. Understanding the evolution of any particular creature requires bringing prior knowledge about the evolutionary branching of all of life and integrating this new specimen into that framework. Organizing knowledge into taxonomies requires transfer of learning, but it can also facilitate transfer of learning. Organizing taxonomies of knowledge allows you to more easily use and acquire knowledge to connect, create, and innovate in further new situations. With Darwin’s undergraduate plant taxonomy, he could surely have been placed in a wide range of ecosystems and provide some level of insight about the local species even if he had never seen those specific plants before. Indeed, for Darwin, his extensive knowledge base on natural history was about to be placed in a brand new situation.

Transfer thinking requires good analogies

In 1828, Darwin’s father was concerned with his son’s lack of drive towards medicine. Charles was abruptly transferred to Christ’s College, Cambridge to study for a Bachelor of the Arts degree, with expectations of becoming an Anglican parson. It was here that Darwin would encounter William Paley’s analogy of the divine watchmaker. Paley famously argued that because the biological world appears to be designed, just as a pocket watch has been designed by a designer, so also, there must be a designer of nature. God acting through natural laws, according to Paley. Darwin’s prior knowledge of natural history and biodiversity allowed him to reflect deeply on Paley’s analogy. Darwin believed Paley’s analogy framed a scientific explanation for God. Still in his early 20s, the young Charles did not yet see the problem in Paley’s logic. For Darwin to cross the next critical threshold of complexity in his thinking about the origin of species, he would need more direct knowledge of the world’s diversity. He would also need lots of time. He would need time to think about the connections between his growing knowledge base and the evolving theories of natural history of his time.

Transfer thinking involves experience, reflection, and synthesis

After some post-graduation adventures, Darwin was invited to travel as a guest naturalist aboard the HMS Beagle. On December 27, 1831, Darwin began a journey sailing across the global south. The ship would follow the South American coastline, crossing the Pacific and Indian oceans, with expeditions on land all along the way. Darwin was experiencing the complexity of life’s diversity first hand. It was on this voyage that Darwin would really begin to polish his ability to transfer his learning from across the domains of natural history to generate novel ideas. Synthesis is merely one form of transfer thinking.

One important example can be found in Darwin’s geological thinking during these travels. Historians of science might say that Darwin was influenced during this time by the then newly published book, Principles of Geology by Charles Lyell. Education scientists might instead say that Lyell’s work created a positive transfer of learning – meaning that Darwin strategically used what he learned in Principles of Geology to facilitate much deeper insights into the domain of biology.

Lyell’s work presented the best synthesis of earth sciences at the time. The book made assertions that the earth was formed much longer than 6,000 years ago, and emphasized that geology developed by the accretion of very slow changes over very long periods of time. On the very first stop of the HMS Beagle to the Cape Verde Islands, Darwin wrote in his notebooks that he was understanding these new worlds by observing the landscape through Lyell’s eyes. Darwin now had a new capacity to transfer his learning from geological theory into insights about the new ecosystems he was exploring. This would be a competence that served him on that voyage and for the rest of his career. As Darwin travelled the southern hemisphere, he gained diverse experience and extensive time for reflection.

Transfer thinking requires a drive to innovate

There is no a priori reason for someone to connect their knowledge about the age of the earth to the design of a finch’s beak, a moth in Madagascar, or any given biological species. The connections Darwin drew between the natural sciences were not so obvious at the time, yet he worked tirelessly to put the puzzle pieces together in a coherent fashion. Transfer thinking requires a drive to innovate.

In the same manner that Darwin, as an undergraduate, would classify plant samples for the museum by extending and integrating the new specimen into his existing taxonomic framework, so Darwin the naturalist began to extend and integrate his knowledge base of geology, biology, and ecology. It is only from the connections between these disciplines that Darwin would see the general principles of evolution.

It is beyond this article to fully document Darwin’s final development of the idea of natural selection, but I will highlight how his transfer of learning abilities positioned him to do so. When Charles Darwin returned from the HMS Beagle voyage in October of 1836 he was a rising celebrity among the scientific community, once again giving him a safe and secure environment to develop his ideas and relationships among family and colleagues.

In 1838, Darwin read Malthus’s An Essay on the Principle of Population, describing the theoretical inevitability of catastrophe if a population rises against a limited food supply. Darwin immediately connected Malthus’s idea on human populations to the non-human struggle for survival in nature. That was the first major transfer of learning Darwin needed before articulating a theory of evolution. The next step was to form an analogy between how farmers select livestock and how nature selects wildlife. As Darwin transferred his knowledge of farming to his knowledge of nature and back again, a deeper understanding of life began to become clear. This new analogy, artificial selection as like natural selection, provided Darwin with a powerful new tool for thinking.

Again, similar to how he used to integrate new species into a taxonomic framework, Darwin could now refine his accumulating conception of evolution by integrating the works of Lyell and Malthus with his analogy of natural selection. By reflecting on the nature of natural selection, Darwin eventually distilled the principles of variation, selection, and inheritance as explanatory of life’s designs to a degree that Paley’s watchmaker hypothesis could not compete with.

Just as life on earth evolved through a slow, incremental accretion in complexity, so also Darwin’s theory of evolution evolved through incremental accretion over his lifetime. It was an idea seeded by the cultural knowledge of the past, shaped by his drives, experiences, and hopes. All children are born with the innate capacity to transfer their learning into new situations, yet many of us reach a plateau. We stop cultivating this strength after we reach basic competence. It was the complex constellation of history, personality, and cultural opportunities that allowed Darwin to continue honing this skill to mastery.

Darwin’s new analogy for life has since been taught to generations of science classrooms. But are most students actually thinking like Darwin did? Is Darwin-style transfer of learning teachable? Can schools cultivate students that are skilled in observation, transdisciplinarity, creative synthesis, or even empathy and emotional intelligence? Darwin’s own story demonstrates there are no short cuts in learning, but perhaps an evolutionary understanding of education can shed some light on these applied questions.

References

1. Darwin, C. (1887). The Autobiography of Charles Darwin.

2. Haskell, E.H. (2001). Transfer of learning: Cognition, instruction, and reasoning. New York: Academic Press.